Deforestation: Grade 9 Understanding for IGCSE Biology 4.18B

Deforestation

Deforestation means the cutting down of mature forest and woodland for non-forestry purposes. No new trees are planted and so the total area of forest decreases. Humans have cut down forests for many reasons and have built their economies on exploiting natural resources. Forests today are cleared to provide wood for logging, to provide land for building homes, for subsistence farmers as well as for commercial growing of crops and cattle farming.

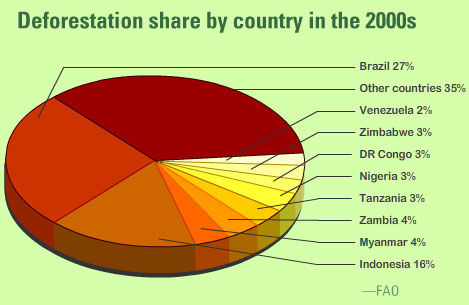

Deforestation happens all the world. (It is worth noting that the only reason there are no European countries on the list below is because all our forests were cleared very effectively some time ago….)

What are the biological consequences of deforestation?

Wherever deforestation occurs, the biological consequences are the same:

- Atmospheric Gases

- Soil Erosion

- Disturbance to the Water Cycle

- Loss of Biodiversity (inexplicably omitted by the people who wrote the specification

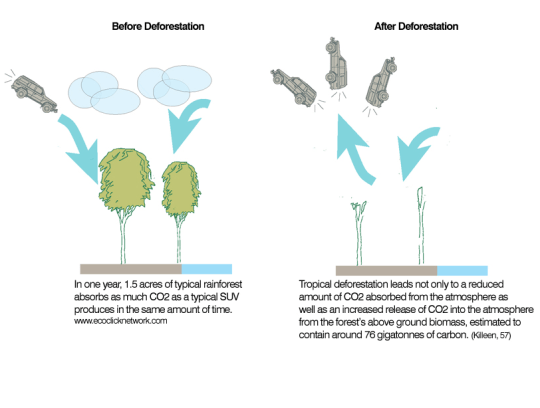

Growing trees have a net uptake of carbon dioxide and a net loss of oxygen due to photosynthesis. Carbon dioxide is a gas that acts as a pollutant in our atmosphere because it is a greenhouse gas. Carbon dioxide concentrations have been rising over the past century and this is leading to permanent and potentially damaging alterations to the earth’s climate system – a process called climate change. Oxygen is the gas that almost all organisms require for their respiration.

In many tropical regions, forests protect the sometimes violent tropical storms from hitting the ground. When forest cover is removed, rainfall hits the soil much harder and this can lead to loss of topsoil in a process called soil erosion. As the water runs through the soil, it will dissolve minerals as it goes, thus leaving the soil that is left denuded of essential minerals for plant growth. This leaching of minerals makes it difficult to use the land cleared for agriculture and so more forest is cleared.

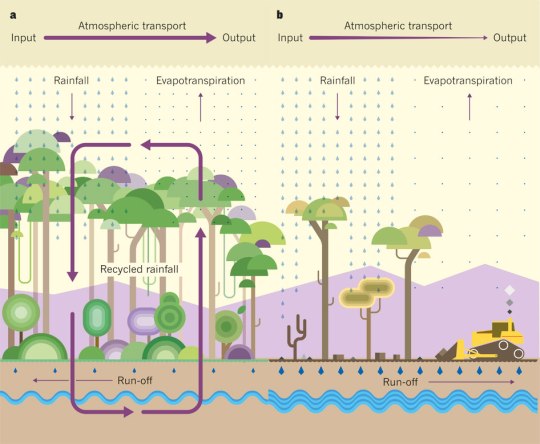

Deforestation also disrupts the water cycle. Trees move large volumes of water a year from the soil into the atmosphere in a process called transpiration. So when trees are lost, less water evaporates from the soil, more water is lost in run-off and so rainfall can be reduced.

The diagram below shows a before and after explanation of how the water cycle is disrupted. (Evapotranspiration is a term for the total water evaporated from a piece of land, combining evaporation directly from the ground and transpiration lost from plants)

There is a final problem with deforestation although the examiners have omitted it from the specification for some inexplicable reason. Forests provide a habitat for a wide variety of animal and plant species. So when forests are lost, species become extinct. This loss of biodiversity is a final terrible consequence of deforestation. 80% of known species live in tropical rainforest so the fact that in the last 50 years, over half of this area has been cleared is a major concern. The rate of loss of rainforest is around 140,000 square kilometres a year although in some parts of the world, the rate of loss is slowing.

Deforestation is a complex issue and a GCSE revision blog like this is not the place to go into the interesting political and cultural details. I would direct you to the WWF site for more information and indeed some ideas as to what we can do to help.

http://wwf.panda.org/about_our_earth/deforestation/