Category: Section 2: Structures and Functions in Living Organisms

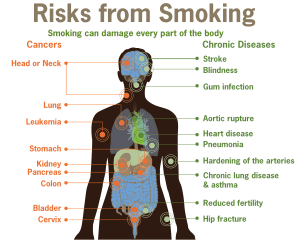

Diseases associated with Smoking: Grade 9 Understanding for IGCSE Biology 2.49 2.67

The health risks of smoking cigarettes and other tobacco products are well understood. But in iGCSE exams, it can sometimes be difficult to work out exactly how much detail the examiner wants, especially on an open-ended question. This blog post is an attempt to demonstrate some of the key areas of understanding that you should be aiming to show in your answers.

Cigarettes contain a wide variety of toxic chemicals: you should focus your understanding on three examples.

Nicotine is the stimulant drug found in cigarette smoke and also the reason smokers can easily become dependent on smoking. Nicotine is rapidly absorbed into the blood in the lungs and it causes an increase in heart rate, an increase in blood pressure and the release of the hormone adrenaline (which has similar effects).

Carbon Monoxide is a poisonous gas that is produced whenever there is incomplete combustion of biological material. Carbon monoxide binds to haemoglobin in the red blood cells in place of oxygen and so the smoker will be transporting less oxygen in her blood, and this leads to a whole load of implications for health.

Tar is the name given to a large number of different chemicals found in cigarette smoke. Tar forms droplets in the smoke which can condense in the airways and alveoli. Many of the chemicals in Tar are carcinogens – that means they promote the formation of cancer. Tar also damages the cilia in the trachea and bronchi and makes the thin walls of the alveoli lose their elasticity and so damage more easily.

Diseases of the Lungs associated with Smoking

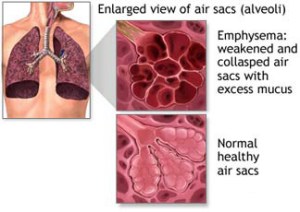

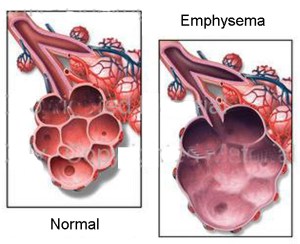

1) Emphysema

Emphysema is a disease in which the thin walls of the alveoli break down. Tar droplets condense onto the alveolar wall, making them rigid and inflexible. Smokers are coughing a great deal to remove the mucus from their lungs and this coughing can cause the sticky, rigid tar coated alveolar wall to degenerate.

A patient with emphysema will have a greatly reduced surface area for gas exchange due to all the collapsed alveoli. So the diffusion of oxygen into the blood would be reduced causing breathlessness and impacting health.

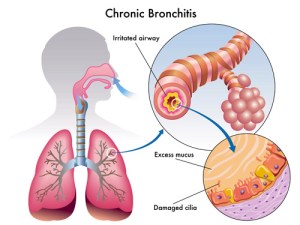

2) Chronic Bronchitis

The bronchi can become inflamed and narrowed due to the overproduction of mucus and the fact that the muco-ciliary escalator does not function to waft mucus up the bronchi. A narrowed bronchus makes breathing harder and compounds the problems of emphysema described above. It also promotes coughing which damages the alveoli still further.

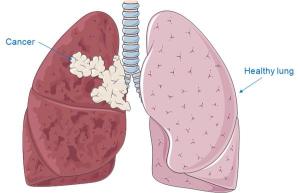

3) Lung cancer

Carcinogens in cigarette smoke can make it much more likely that cells in the lungs and airways develop mutations that lead to cancer. Cancer is a disease in which cells start to divide out of control to form a tumour and then cells in the tumour break off and travel round the bloodstream to form secondary tumours elsewhere in the body. Lung cancers can be hard to treat and are a common cause of early death in cigarette smokers.

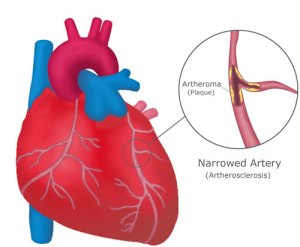

Diseases of the Cardiovascular System associated with Smoking

It is not just the lungs that are affected in patients who smoke. Cigarette smoking is a significant risk factor in the commonest cause of death in the UK: coronary heart disease (CHD)

CHD is a disease in which the arteries that supply the cardiac muscle in the heart (the coronary arteries) get narrowed due to the build up of fatty plaque in their walls. This is a condition called atherosclerosis. A narrowed coronary artery means that an area of cardiac muscle is starved of oxygen and so can die. This may interfere with the electrical coordination of the heart beat causing a cardiac arrest or heart attack.

Patients who smoke have a higher blood pressure than normal due to the stimulant effects of nicotine. A high blood pressure makes the early damage to the arterial lining more likely as well as making the blood more likely to clot. Blood clots form in the final stages of the disease around the plaque and can complete block the blood vessel. CHD is a major cause of death across the world and it is well known that stopping smoking can do a great deal to lower a patient’s risk of this potentially deadly disease.

Breathing: Grade 9 Understanding for IGCSE Biology 2.46 2.47

Breathing is the movement of air in and out of the lungs. It is a small point but you must be careful with your language in answering questions in this topic. Meaning is lost if words are not used correctly: for example often candidates write than “oxygen is breathed in and carbon dioxide breathed out….” Can you see why this is not correct and actually muddles your understanding of the process?

(Please don’t confuse breathing with gas exchange which is the diffusion of oxygen and carbon dioxide in and out of the blood, nor with respiration which is a series of chemical reactions happening in all cells in which food molecules are oxidised to release energy for the cell)

So back to breathing – the movement of air in and out of the lungs…..

1) What is the pathway air follows to get from the atmosphere and into the alveoli in the lung?

The trachea is the main tube that carries air into the lungs. It has a ciliated epithelium lining – these cilia waft mucus and foreign particles up to the top of the trachea and then the mucus is swallowed into the stomach and any bacteria trapped in the mucus are killed. The trachea is also strengthened by C-shaped rings of cartilage that prevent the tube collapsing when the air pressure inside drops. The trachea branches into two tubes called bronchi, one going to each lung. The bronchi branch over and over again into smaller tubes called bronchioles and ultimately the smallest bronchioles end in a cluster of microscopic air sacs called alveoli. This whole structure is called the Bronchial Tree.

2) What causes air to move in and out of the lungs in breathing?

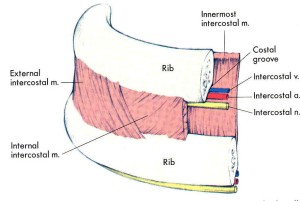

The movement of air into and out of the lungs is brought about by the action of two muscles: the diaphragm, a dome-shaped muscle that separates the thorax from the abdomen, and the two sets of intercostal muscles. This is an easy area to get confused as there are plenty of similar words and precision in explanation is vital to clear understanding…..

Breathing in (Inhalation) is the active stage in breathing. This means that under normal condition it is the stage in which the muscles contract. During inhalation, the diaphragm contracts. This contraction causes it to change shape from the dome-shape at rest to a flattened shape. This change in shape of the diaphragm increases the volume of the thorax (in fact it is the volume of the pleural space between the two pleural membranes that is significant but we might skip over this for simplicity….).

If the volume of a gas increases, the pressure decreases (Boyle’s Law I seem to remember from boring Physics lessons a long time ago). If the pressure in the thorax decreases, it may drop below atmospheric pressure and so air can be pushed into the alveoli through the bronchial tree by the higher atmospheric pressure.

Breathing out (Exhalation) is a passive process. The diaphragm is a most unusual muscle as it is very elastic. This means that when it relaxes, it springs back to its original dome-shape through elastic recoil. This movement decreases the volume of the thorox, thus increasing the pressure and if the pressure rises above atmospheric pressure, air will be pushed out of the alveoli.

3) What role do the Intercostal muscles play in breathing?

The intercostal muscles are two sets of muscles that are found between the ribs. Contraction of these muscles can either pull the rib cage up and out, or push the rib cage down and in. The muscles on the outside are called the external intercostal muscles and the ones on the inside are called internal intercostal muscles.

When you are breathing at rest the rib cage does not move at all. (I hope everyone reading this post is calm, relaxed and not hyperventilating in panic over upcoming exams….) As you are breathing at rest the only muscle involved is the diaphragm (see section above) as you are only moving about half a litre of air in and out with each breath. But there are situations in which this tidal volume has to increase and that is when the intercostal muscles come into their own.

The two sets of intercostal muscles are antagonistic – when one contracts the other relaxes.

If you need to take a big breath in, the external intercostals will contract at the same time as the diaphragm. The external intercostals pull the ribcage up and out, thus increasing even further the volume of the thorax, thus dropping the air pressure even more in the thorax, allowing more air to come in. When you come to breathe out, the external intercostal muscles will relax and gravity will allow the ribcage to fall back down to its original position.

But I hear you say…. “What happens if you are lying down or upside down? How can the ribcage get back to its original position without the help of gravity?” Well don’t worry – you have the internal intercostals which in extreme situations will contract during exhalation to push the ribcage down and in…

I suggest you draw up a table to summarise the process of breathing. Give inhalation and exhalation a column each, and the rows of the table should be diaphragm, external intercostals, internal intercostals… Tweet me a photo of your table if you want me to have a look…

Demonstrating Carbon Dioxide production in Respiration of Yeast 2.39

Yeast is a single celled fungus that can respire aerobically when oxygen is available and anaerobically in the absence of oxygen.

Aerobic respiration in yeast:

Glucose + Oxygen ======> Carbon dioxide + Water

Anaerobic respiration in yeast:

Glucose ======> Ethanol and Carbon dioxide

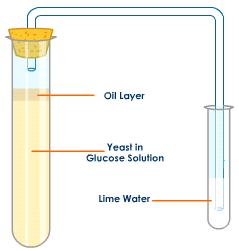

Both forms of respiration produce carbon dioxide as a waste product so how could this be demonstrated experimentally?

This is the simplest set up that could demonstrate this. Lime water will go cloudy in the presence of carbon dioxide. Glucose solution is needed to provide the reactant sugar for the yeast to respire. The oil layer on the top is to prevent the diffusion of oxygen from the air into the Yeast in Glucose solution, this ensuring anaerobic respiration will occur.

What experimental factors could be altered in this set up?

Well assuming you keep the volume and concentration of lime water constant, the time taken for the limewater to go cloudy could be measured under differing conditions: the faster the time, the faster the rate of respiration. The experimenter could investigate the effect of changing the temperature, the pH or the concentration of glucose solution used. Make sure you understand how and why changing each of these factors might affect rates of respiration in yeast.

Respiration experiments: Grade 9 Understanding for IGCSE Biology 2.39

There is a syllabus point in the iGCSE Respiration section that asks candidates to know about an experiment that demonstrates heat production in respiration. This must be one of the least interesting experiments ever devised but here goes…..

Respiration is the chemical process occurring in all cells in which food molecules are oxidised to release energy for the cell. Cells need energy for a whole variety of things – active transport of molecules across the cell membrane, muscle contraction, movement of materials around the cytoplasm, cell division, many metabolic reactions etc. In fact, much of the energy released from glucose molecules in respiration is not “useful energy” for the cell but is given off as heat, a waste product. In warm-blooded animals such as humans, this heat energy is used to maintain our body temperature at around 37 degrees Celsius.

How can you demonstrate heat production in respiration?

The germinating seeds in the vacuum flask on the left are respiring because they are alive. The boiled seeds in the vacuum flask on the right will not be respiring because they are dead – boiling will denature all the enzymes needed for metabolism, The thermometer on the left will show a rise in temperature, the one on the right will stay the same. The flask on the right with the boiled seeds is a control. Vacuum flasks are used to insulate the seeds and so prevent heat loss.

The experiment is as simple as that. If the examiners wanted to ask a question on this, I guess they would give you the set up, ask about the design of the experiment, ask about which variables you might control and perhaps what conclusions could be drawn.

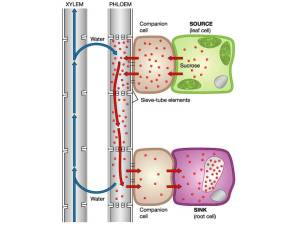

Phloem Transport: Grade 9 Understanding for IGCSE Biology 2.53

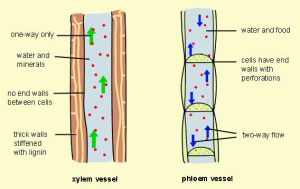

Most of the work you do on transport in plants concerns the movement of water and minerals from the roots to the leaves of the plants in xylem vessels. (see previous post on xylem transport) You should understand what transpiration is, and how the properties of water allow a transpiration pull provide the energy to move large volumes of water up the xylem in the plant.

But what about the second plant transport tissue phloem? How does it differ from xylem in both structure and function?

Well structurally the tissues are very different. Xylem vessels are large, dead, empty thick-walled cells with cell walls strengthened with lignin. The transport cells in phloem are called sieve-tubes. Phloem sieve tubes are living cells with thin cell walls.

In xylem vessels the end walls break down completely but in phloem sieve tubes, the end walls are filled with many holes forming a structure called a sieve plate. Each phloem sieve tube has a smaller cell called a companion cell alongside and both these two cells must be alive for phloem transport to occur.

What is transported in phloem sieve tubes?

Plants transport the products of photosynthesis (food molecules) up and down the stem in phloem. The main carbohydrate transported is sucrose but phloem cells also contain lots of amino acids and a few other sugars.

The mechanism by which these sugars are moved around the plant is less well understood than for water movement in xylem. Translocation is an active process and requires energy from respiration in the cells. It is possible that a bulk flow exists as shown in the diagram below, but this mechanism cannot be the whole story….. Can you think why? Post a comment if you want to explain some of the difficulties with this theory…..

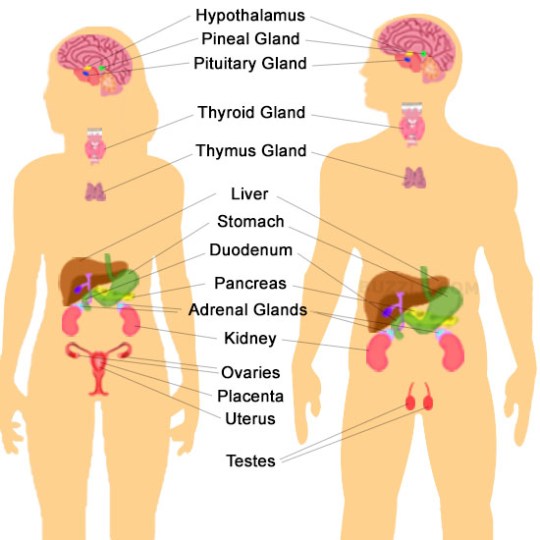

Hormones: Grade 9 Understanding for IGCSE Biology 2.94 2.95B

Hormones are defined as “chemicals produced in endocrine glands that are secreted into the bloodstream and cause an effect on target tissues elsewhere in the body”. They play a wide variety of roles in the healthy functioning and development of the body.

The iGCSE specification only really mentions a small number of hormones so these are the ones I will focus on in this post.

ADH (anti-diuretic hormone) (Separate Biologists only – not Combined Science)

ADH is secreted into the blood by an endocrine gland at the base of the brain called the Pituitary Gland. The stimulus for the release of ADH into the blood comes from the hypothalamus (a region of brain right next to the pituitary gland) when it detects that the blood plasma is becoming too concentrated. This might be caused by the body becoming dehydrated due to sweating. ADH travels round the body in the blood until it reaches its target tissue which are the cells that line the collecting ducts in the nephrons in the kidney. ADH increases the permeability of the connecting duct walls to water, thus meaning more water is reabsorbed by osmosis from the urine in the collecting duct and back into the blood. This results in a small volume of concentrated urine being produced.

Adrenaline

Adrenaline is secreted into the blood by the adrenal glands in situations of danger or stress.. The adrenals are found just above the two kidneys on the back of the body wall. Adrenaline secretion is controlled by nerve cells that come from the central nervous system. Adrenaline is often described as the “fight or flight” hormone as its effects are to prepare the body to defend itself or run away from danger. There are receptors for adrenaline in many target tissues in the body but some of the most significant effects of adrenaline are:

- affects the pacemaker cells in the heart causing an increase in heart rate

- shifts the pattern of blood flow into muscles, skin and away from the intestines and other internal organs

- decreases peristalsis in the gut

- causes pupils to dilate in the eye

- increases breathing rate in the lungs

- promotes the passing of urine from the bladder

Insulin

Insulin is a hormone made in the islets of Langerhans in the pancreas. It plays a vital role in the homeostatic control of the blood sugar concentration. The pancreas will secrete insulin into the blood when the blood glucose concentration gets too high. There are many cells in the body with insulin receptors but the main target tissue for insulin is the liver.

Insulin causes the liver (and muscle) cells to take glucose out of the blood and convert it into the storage polysaccharide glycogen. This results in a lowering of the blood glucose concentration: a good example of the importance of the principle of negative feedback in homeostasis

Testosterone

Testosterone is a steroid hormone made by cells in the testes of males. It is the main hormone of puberty in males resulting in the growth of the reproductive organs at puberty as well as the secondary sexual characteristics (pitch of voice lowering, muscle growth stimulated, body hair grows etc.)

Oestrogen

Oestrogen is a steroid hormone made by the cells in the ovary that surround the developing egg cell in the first half of the menstrual cycle. In puberty it causes the development of the female secondary sexual characteristics (breast growth, change in body shape, pubic hair etc.) but in the menstrual cycle, oestrogen has a variety of important effects. It stimulates the rebuilding of the uterine endometrium (or lining) to prepare the uterus for the implantation of an embryo. Oestrogen also affects the pituitary gland and can cause the spike in LH concentrations that trigger ovulation on day 14 of the cycle.

Progesterone

Progesterone is also made in the ovary but at a different time in the menstrual cycle. It is secreted by cells in the corpus luteum, a structure found from day 14 onwards after the egg has been released in ovulation. Progesterone has two main target tissues: it maintains the thickened lining of the endometrium in the uterus ready for implantation. Progesterone also causes the pituitary gland to stop secreting the hormones FSH and LH so a new cycle is never started. It is for this reason that progesterone can be used in women as a contraceptive pill.

FSH (Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (Separate Biologists only – not Combined Science)

FSH is a hormone released by the pituitary gland underneath the brain. The target tissues for FSH are in the testis (males) and ovaries (females). In males FSH plays a role in the growth of the testes allowing sperm production to start. In females, FSH is the hormone released at the start of the menstrual cycle that causes one of the immature egg cells in an ovary to grow, develop and so become surrounded by follicle cells prior to ovulation.

LH (Luteinising Hormone) (Separate Biologists only – not Combined Science)

LH is a second reproductive hormone released by the pituitary gland into the bloodstream. In males, it stimulates the production of testosterone in the testes. In females, it is released only on days 13 and 14 of the menstrual cycle and it is the hormone that triggers ovulation.

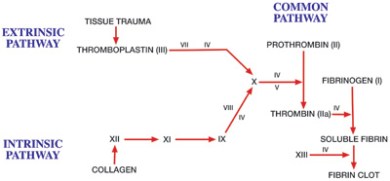

Platelets and Blood Clotting – Grade 9 Understanding for iGCSE Biology 2.64B

There is a specification bullet point in bold (paper 2 only) about blood clotting and the role of platelets, and students are sometimes not sure to what level of detail is needed for a full GCSE understanding of this topic. Well the good news is that the only questions I can recall are very straightforward indeed. But in this post I will give you a little more detail than the minimum needed for A* answers so that you can be confident you are completely clear on this part of the specification.

Why does blood need to clot?

Capillaries have a very thin wall (one cell thick in fact) so can easily tear and get damaged. This means that damage causes blood to leak into tissues forming a bruise and if the skin is broken, blood can be lost from the body entirely. Blood clotting is the response in the blood that ensures that blood loss is minimised and also that the time micro-organisms have to get into the blood stream is kept as short as possible. The surface of the skin is covered with millions of pathogenic organisms (mostly bacteria) all waiting for the chance to get into the blood stream through a cut or tear.

What are platelets?

Platelets are small fragments of cells found in bone marrow that then get into the blood and are carried round in the plasma. They are not entire cells as they lack a nucleus but they do play an essential role in blood clotting.

How does blood clotting work?

When the lining of a capillary is broken, platelets initially stick to the site of damage. They then trigger a series of reactions in the blood plasma that causes a clot to form. The details of how this works are too complicated to go into here but the basic idea is that in the blood plasma are a whole family of proteins called clotting factors. There is a cascade of reactions such that one clotting factor is activated and in turn, activates the next in the sequence. The final reaction in the clotting cascade is that a soluble protein called fibrinogen is converted into an insoluble fibrous protein called fibrin. Fibrin forms a mesh around the platelet cap covering the site of damage and this mesh traps red blood cells forming the final clot.

The roman numerals on the diagram above refer to clotting factors and each in turn is activated. You can see the final stage of the cascade is that soluble fibrin is converted into the fibrin clot.

Many of you will know of the disease where blood doesn’t clot called haemophilia. The commonest type of haemophilia is a genetic disease where patients cannot produce clotting factor VIII. This means one step in the clotting cascade does not work and so the blood cannot clot normally.

(Extension idea: find out the link between Haemophilia, the British Royal family and the 20th century history of Russia)

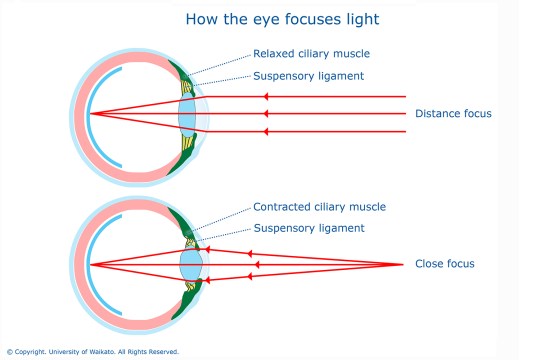

Understanding the Eye to Grade 9 at GCSE Biology (part 2) 2.91 2.92

In the first blog post on this series, I described the pupil reflex in the eye. If you remember this involved the circular and radial muscles in the iris contracting and relaxing in an antagonistic fashion to alter the size of the pupil. You should understand why the pupil size needs to altered and what state the two sets of muscles are in varying light intensities.

But there is a second reflex in the eye totally separate from the pupil reflex and it is to do with focusing. This reflex is sometimes called accommodation but as this is a word I can’t spell, I prefer to call it focusing…. The retina at the back of the eye contains the photoreceptors. There are two types of photoreceptor in the retina (rods and cones) and these are individual cells that can detect the light and then send a nerve impulse in the optic nerve that goes to the brain.

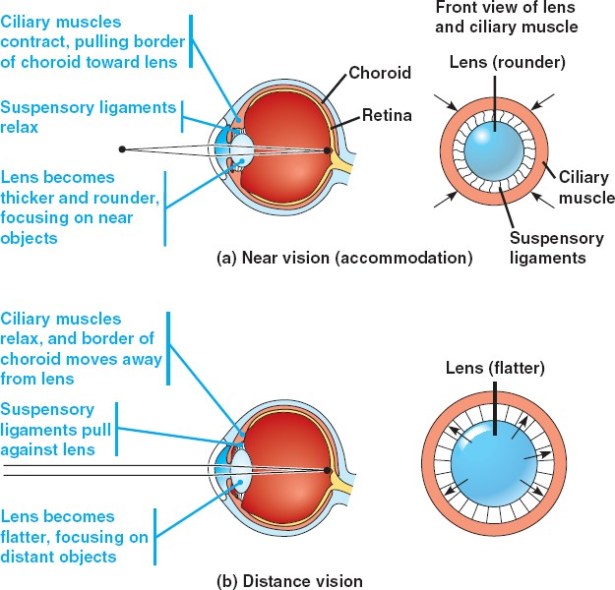

Focusing in the Eye (this is quite complicated and needs careful, slow reading)

When the eye views objects from differing distances away, the degree the light has to be bent to produce a focused image will vary. Light coming from near objects will be diverging (the rays will be moving away from each other) and so to focus the light onto the retina, a large amount of bending (or better still refraction) will be needed. Light rays coming from far away objects are almost parallel when they hit the eye so the degree of refraction required is much less.

How can varying degrees of refraction be achieved in the eye?

Well as the diagram above shows, this is brought about by changing the shape of the lens. A short fat lens will refract (or bend) the light more than a long thin one. (If you want an explanation for why this is, you need to ask a Physics teacher – it is to do with the angle of curvature of the lens and the refractive indices of the liquids in the eye compared to the lens…….)

The lens in its default state is short and fat. This means that with no tension pulling it out of shape it will adopt the short fat shape suitable for viewing near objects.

How can the lens be pulled out of its default short fat shape?

Now this is the bit where people get confused. Read this section really carefully, check with your own notes and revision notes and make sure you have got this all the right way round! Here goes…..

There is a ring of muscle that surrounds the lens in the eye called the ciliary muscle. (Please make sure you don’t confuse this with the circular muscles in the iris) The ciliary muscle doesn’t attach to the lens directly but is attached to the lens via some strong and inelastic ligaments called the suspensory ligaments. Tension in the suspensory ligaments can pull the lens from its default short, fat shape into the long this shape needed to view far away objects.

When the ciliary muscle contracts, it shortens. This effectively moves it closer to the lens and so any tension in the suspensory ligaments is released as the ligaments go slack. Slack ligaments mean the lens adopts its short fat shape.

When the ciliary muscle relaxes, this changes its position to increase the tension in the suspensory ligaments. Taut suspensory ligaments (caused by the relaxed muscle) will pull the lens into a long thin shape.

You can easily see why people get confused here: a contracted ciliary muscle leads to slack suspensory ligaments and vice versa.

One way you can improve your understanding is to be really precise with your use of language. The ciliary muscle is a muscle (no honestly it is) and as you know, muscles can either contract or relax. Suspensory ligaments cannot contract or relax but their tension can be altered from taut (loads of tension) to slack.

So to summarise this complex sequence of events:

Looking at a far object

- Lens needs to be long and thin

- as light rays are almost parallel as they hit the eye

- and so require little bending.

- To pull the lens long and thin requires

- suspensory ligaments to be taut

- and this is achieved by the ciliary muscle relaxing.

Looking at a near object

- Lens needs to be short and fat

- as light rays are diverging as they hit the eye

- and so require a lot of bending.

- The lens will adopt a short, fat shape with

- no tension in the suspensory ligaments (the ligaments are slack)

- and this is achieved by contracting the ciliary muscle.

You can easily check your understanding here because it is much more tiring on the eye to look at a near object. If you sit on a sunny beach after all your GCSEs are finished, staring out to sea in a contemplative manner wondering how you managed to work so hard through the revision period, you could continue like this for hours. But if you try staring at your finger a few centimetres from your face for even a few seconds, your eye starts to tire. In the former scenario the ciliary muscle is relaxed and so not expending any energy but in the latter, the ciliary muscle is contracted, using energy from respiration and so can get tired.

Please comment me on this blog post with any questions – I will do my best to respond to anyone who gets in touch.

Good luck and keep working hard!

Understanding the functioning of the Eye to Grade 9 for Biology IGCSE (part 1) 2.91, 2.92

There are two reflex responses in the eye that you need to fully understand for A* levels at iGCSE. It is really easy to get them confused but I am going to put on consecutive blog posts so you can see the similarities and differences easily.

The first is a reflex called the “Pupil Reflex” which is to ensure an appropriate amount of light enters the eye in both bright and dim light. The only structure in the eye involved in the Pupil Reflex is the Iris. The second reflex explained in part 2 is the “Focusing Reflex” (or sometimes Accommodation) which makes sure that light entering the eye from objects at different distances away is focused correctly onto the retina. The structures involving in Focusing are the Lens, Ciliary Muscle and Suspensory Ligaments.

The Pupil Reflex

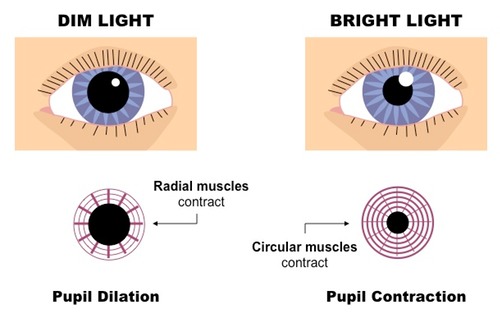

1) Why do we need a pupil reflex?

The eye has evolved a mechanism to ensure that the amount of light entering the eye can be adjusted. In bright light you need to limit the amount of light to prevent the light damaging the light-sensitive cells in the retina (a process called “bleaching”) and this is done by making the pupil at the front of the eye small. A small pupil would be useless for vision in low light intensities as then not enough light would get to the retina and vision would be very poor. So in dim light (low light intensities) the pupil is enlarged to allow a maximal amount of light into the eye.

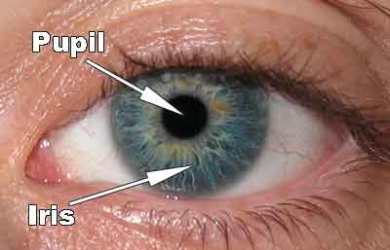

2) What is the Pupil?

The pupil isn’t really a structure at all as it is simply a circular hole in the iris. The iris is a coloured muscular disc at the front of the eye.

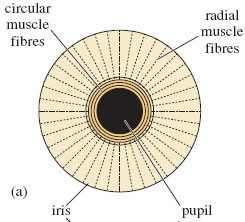

The iris has two sets of antagonistic muscles in it that can contract or relax to change the diameter of the pupil. There are radial muscles arranged like the spokes of a bicycle tyre and also circular muscles in the iris as shown in the diagram below.

3) How do the muscles in the iris bring about the pupil reflex?

Remember muscles can only contract or relax. When the radial muscles contract (shorten) they will pull the iris into a narrower shape so the pupil gets much wider. When the circular muscles contract, they will squeeze the pupil smaller so the pupil will narrow.

So you need to basic understand the state of these two sets of antagonistic muscles in both bright and dim light.

Bright light – circular muscles contracted, radial muscles relaxed, pupil small

Dim light – circular muscles relaxed, radial muscles contracted, pupil large

Gas Exchange in Plants – Grade 9 Understanding for IGCSE 2.40B, 2.41B, 2.44B, 2.45B

The topic of gas exchange in plants is often tested in exams because it can be a good discriminator between A grade and A* grade candidates. If you can master the understanding needed for these questions, important marks can be gained towards your top grade.

Firstly you must completely remove from your answers any indication that you think that plants photosynthesise in the day and respire at night. Even typing this makes me feel nauseous…. Yuk? Respiration as you all know happens in all living cells all the time and so while the first half of the statement is true (photosynthesis only happens in daytime), respiration happens at a steady rate throughout the 24 hour period.

Although the equations above make it look like these two processes are mirror images of each other, this is far from the truth.

How can gas exchange in plants be measured?

The standard set up involves using hydrogen carbonate indicator to measure changes in pH in a sealed tube. In this experiment an aquatic plant like Elodea is put into a boiling tube containing hydrogen carbonate indicator. The indicator changes colour depending on the pH as shown below:

- acidic pH: indicator goes yellow

- neutral pH: indicator is orange

- alkaline pH: indicator goes purple

a) If the tube with the plant is kept in the dark (perhaps by wrapping silver foil round the boiling tube), what colour do you think the indicator will turn? Explain why you think this.

b) If the tube with the plant is kept in bright light, what colour do you think the indicator will turn and why?

c) If a control tube is set up with no plant in at all but left for two days and no colour change is observed, what does this show?

In order to score all the marks on these kind of questions, there are two pieces of information/knowledge you need to demonstrate. You need to show the examiner that you understand that carbon dioxide is an acidic gas (it reacts with water to form carbonic acid) and so the more carbon dioxide there is in a tube, the more acidic will be the pH. As oxygen concentrations change in a solution, there will be no change to the indicator as oxygen does not alter the pH of a solution.

Secondly you need to show that you understand it is the balance between the rates of photosynthesis and respiration that alters the carbon dioxide concentration. If rate of respiration is greater than the rate of photosynthesis, there will be a net release of carbon dioxide so the pH will fall (become more acidic). If the rate of photosynthesis in the tube is greater than the rate of respiration, there will be a net uptake of carbon dioxide (more will be used in photosynthesis than is produced in respiration) and so the solution will become more alkaline.

So to answer the three questions above I would write:

a) The indicator will turn yellow in these conditions. This is because there is no light so the plant cannot photosynthesise but it continues to respire. Respiration releases carbon dioxide as a waste product so because the rate of respiration is greater than the rate of photosynthesis, there will be a net release of carbon dioxide from the plant. Carbon dioxide is an acidic gas so the pH in the solution will fall, hence the yellow colour of the solution.

b) The indicator will turn purple in these conditions. This is because the bright light means the plant photosynthesises at a fast rate. Photosynthesis uses up carbon dioxide from the water. The plant continues to respire as well and respiration releases carbon dioxide as a waste product. As the rate of photosynthesis is greater than the rate of respiration in these conditions there will be a net uptake of carbon dioxide. Carbon dioxide is an acidic gas so if more is taken from the solution than released into it, the pH in the solution will rise as it becomes more alkaline, hence the purple colour of the solution.

c) This shows that without a living plant in the tube there is nothing else that can alter the pH of the solution. It provides evidence that my explanations above about the cause of the colour change is correct.