Cell Division part I: Grade 9 Understanding for IGCSE 3.15, 3.28, 3.29

At the beginning of March each year, I get my Y11 classes to draw up a list of topics they want to go through again in revision. Cell Division is always there and it is not difficult to see why. Mitosis doesn’t make any sense unless you understand the concept of homologous pairs of chromosomes and I think you already know that very few iGCSE students do…… (Please see the various posts and videos on the blog on this topic before attempting to understand mitosis)

But there is actually very little to fear in the topic of cell division. If your teacher has told you about the various stages of mitosis that’s fine but you will not be asked to recall them in the exam, at least not if you are studying EdExcel iGCSE. So in this post I am going to try to focus on the key bits of understanding you need rather than bombarding you with unnecessary details.

1 Chromosomes come in pairs

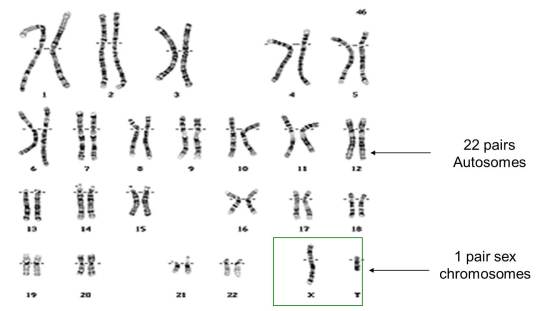

This is the main idea you need before you start. In almost all sexually-reproducing organisms the cells are DIPLOID. This means that however many different sized chromosomes they have, in each cell there will be pairs of chromosomes (called homologous pairs)

So human cells contain 23 pairs of chromosomes (46 in total)

Remember that the number 46 only applies to humans. Other species have very different numbers of chromosomes in each cell (see table below)

So doves have 8 pairs of chromosomes, dogs have 39 pairs of chromosomes, rats 21 pairs of chromosomes. The important point is not how many pairs each organism has but that they all have chromosomes that come in pairs!

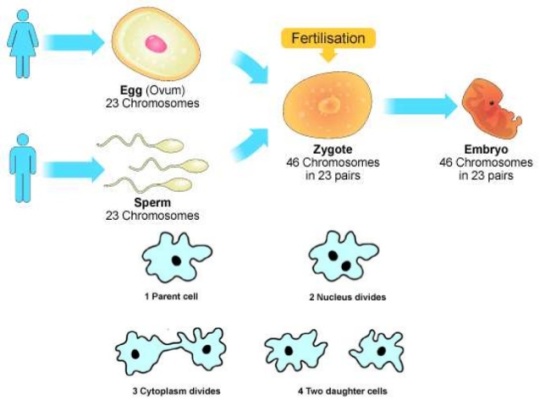

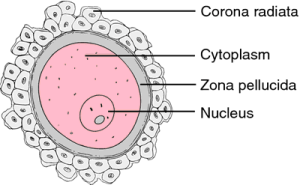

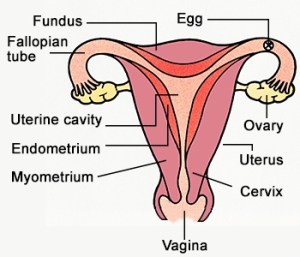

The chromosomes any individual possesses is determined at the moment of fertilisation. Sperm and Egg cells (gametes) do not have pairs of chromosomes. They are the only cells in the body that are not diploid. Gametes only have one member of each pair of chromosomes. Cells which only have one member of each pair of chromosomes are called HAPLOID cells.

So every cell in the body is diploid and genetically identical apart from the gametes which are haploid.

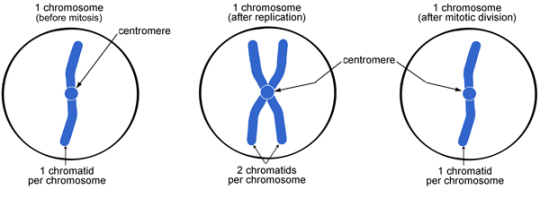

2 Organisms that reproduce sexually need two different types of cell division

The fertilised egg (zygote) is a diploid cell. It has pairs of chromosomes that originate one from each parent via the gametes. Every cell division in growth and development of the embryo and foetus until birth, every cell division in growth and repair after birth always produces two genetically identical and diploid cells from the one original cell. This cell division that produces genetically identical diploid cells is called Mitosis.

Gametes (sperm and egg cells) need to be made by a different process. If gametes were diploid then there would be a doubling of the chromosome number every generation and that clearly wouldn’t do. So a different way of dividing the nucleus has evolved. It doesn’t produce genetically identical diploid cells but produces gametes that are haploid and genetically unique. This process is called Meiosis and is only used in the production of gametes.

3 Mitosis is involved in growth, repair, asexual reproduction and cloning

Any process in the body in which the outcome required is the production of genetically identical diploid cells will use mitosis. (It is not too complicated an idea to see that if you don’t need to make gametes and fuse them together in fertilisation, you can just copy cells by mitosis over and over again. All the daughter cells will be exact copies of each other and diploid.

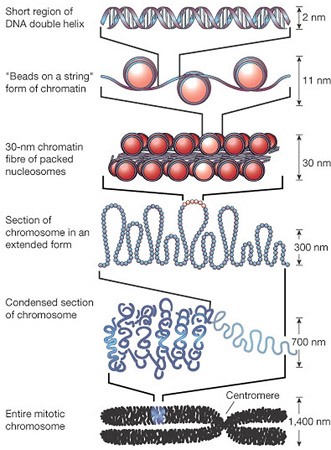

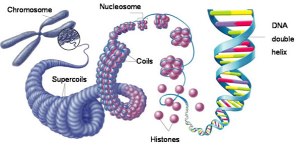

Now I know this post is not going to satisfy everyone. I know some of you will want to read about the cell cycle, prophase, metaphase, centrioles, spindle fibres and the condensation of chromosomes, chromatids being pulled apart etc. etc.) And just for you, I will write a post later today on the details of Mitosis….. But please remember that if you are using the blog to revise for exams, none of this second post is necessary and none of it will be tested in the Edexcel iGCSE paper. If you are doing revision, focus on the key understanding ideas discussed above. And as always, please leave a reply below to ask questions, comment or leave feedback – all comments welcome!