Category: Section 2: Structures and Functions in Living Organisms

Plant Tropisms: Grade 9 Understanding for IGCSE Biology 2.83 2.84 2.85

Plant Sensitivity

Sensitivity is a characteristic of all living organisms. It means the ability to detect and response to changes in the environment. When most students think of sensitivity they immediately think of receptors and the nervous system of mammals. In this post, I will summarise a few ways that plants are able to detect and respond to changes in their environment.

What stimuli are plants able to detect?

Stimulus Response

Light shoot grows towards light

Gravity root grows in the direction of gravity

Water roots will grow towards moisture

Touch some plants can grow towards touch

There are others such as day length, presence of certain chemicals and temperature too. But you can see that for all the stimuli in the table above, the response is by altering the pattern of growth. Animals often respond to stimuli with muscle contractions leading to movement. Plants have no equivalent of muscle tissue of course and so they respond through growth.

A tropism is a growth response in a plant in which the direction of the stimulus determines the direction of growth in the plant.

For example, positive phototropism would be the term used when a growing shoot will grow towards unidirectional sunlight. Growing roots will show negative phototropism when they grow away from light.

How is positive phototropism in a growing shoot brought about?

Plant growth is controlled by a family of chemicals called Plant Growth Substances (PGS) – in the past these were sometimes called plant hormones. The most important PGS and indeed the only one you need to know about for iGCSE is called Auxin. This chemical is made in the tip of the growing shoot and when it diffuses down a millimetre or two to the growing region, it can stimulate growth in two ways. Auxin causes cells in the shoot to divide by mitosis and also influences the cell wall of the plant cells allowing them to elongate. The net effect of this is to stimulate growth.

Auxin is actually a chemical called Indole Acetic Acid (IAA) and sometimes you will see it referred to by this name.

The detailed mechanism of positive phototropism in shoots is not well understood but we do know that if the shoot has brighter light on one side than the other, auxin will be moved towards the darker side of the shoot. This lateral redistribution of auxin allows the darker side to grow faster, so the shoot bends towards the light.

- Phototropism in plants is brought about by a chemical called AUXIN or IAA.

- Auxin is made in the tip of the growing shoot and diffuses down the stem towards a region of cell growth.

- If the shoot is growing in unidirectional light, the auxin will accumulate on the dark side of the shoot.

- Auxin stimulates mitosis in the growing region as well as causing individual cells to elongate.

- For this reason the darker side of the shoot will grow faster and so the shoot will bend towards the light.

Geotropism – a growth response to gravity

We know that the growing root and shoot are also able to detect gravity. A growing root will always grow downwards (positive geotropism) and the shoot upwards (negative geotropism). How are these responses brought about?

Well it’s our old friend auxin again…..

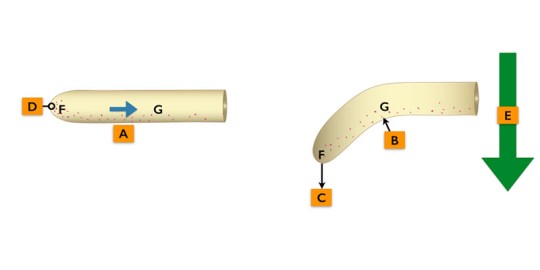

This diagram shows auxin moving downwards in a shoot under the influence of gravity. The lower side has a higher concentration of auxin and so grows faster. This results in negative geotropism in the shoot: it will grow in the opposite direction to gravity.

As far as I know, no-one really understands how the growing shoot and root are able to detect the direction of gravity. No-one really knows how the lateral redistribution of auxin due to light happens either…. There are still plenty of unknowns in this topic!

This final diagram shows positive geotropism in a growing root. It is positive geotropism because the root grows in the direction of gravity. If auxin accumulates on the lower side of the growing shoot and root (and it does) how does this work? Well it turns out that while auxin stimulates growth in the shoot, the same chemical inhibits growth in the root. So the diagrams above show auxin being produced at the tip (D) and accumulating on the lower side of the root (B). Auxin inhibits the growth of the root causing less growth on this side, so the root bends downwards.

Plant Tropisms – I can’t make myself do it….. 2.83 2.84 2.85

Is there a single topic more likely to strike fear into the heart of a GCSE Biology student? Everyone hates plant tropisms – students because it seems dull, and teachers because it seems like 19th century science and none of us can see for one second why it should appear in 21st century specifications….. I will write a post about auxins, phototropism and geotropism for your all but it will take me a day or two to build up to it….. As I said, everyone hates tropisms.

“How to build a human heart” video

Great video introduction to Nervous Systems: Grade 9 Understanding for IGCSE Biology 2.86

You all should really subscribe to the Crash Course YouTube channel. Some of their output is perhaps more suitable for A level students, but the scientific content is great. I really like the presentation too but it is quite American (I hope my readers in the US will understand….) so I am prepared for people to disagree….

Anyway here is the introduction video to Nervous Systems: great for my two Year 11 groups just now. Enjoy.

Thermoregulation: Grade 9 Understanding for IGCSE Biology 2.93

Homeostasis is a term that means maintaining a constant internal environment in spite of changes in the external environment. Many variables in the body are regulated by homeostasis but the two control systems specifically mentioned in your specification for iGCSE are osmoregulation (regulation of water balance) and thermoregulation (regulating of body temperature)

I have looked at osmoregulation in a previous post but in this final post for half term 2015, I will give a few details about thermoregulation.

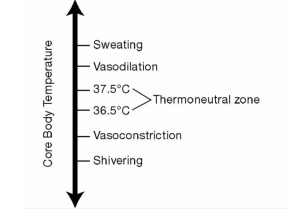

Thermoregulation means to maintain the core body temperature at a set value. This can be energetically very costly as the animal has to respire at a much higher rate to release the heat needed to warm the body, but it has allowed mammals and birds to colonise habitats that would be inaccessible to all poikilothermic (cold-blooded) animals.

Why regulate body temperature?

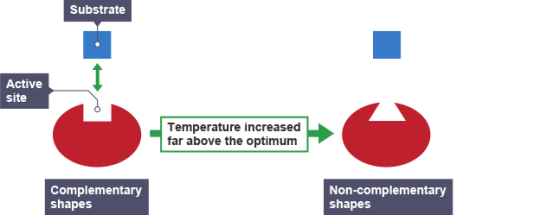

All metabolic reactions in the body are catalysed by enzymes. If the body temperature falls too low below the set value, the rate of an enzyme-controlled reaction will drop, and this would be a problem as metabolic reactions would happen too slowly. If the temperate goes much above the optimum temperature, then the enzymes that catalyse all the reactions in cells would denature. This means they will change their shape so that the “lock and key” mechanism of catalysis cannot work at all.

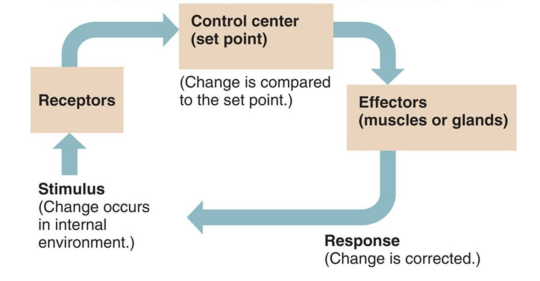

In any homeostatic control system there will be three components:

- Sensors (where the variable is measured)

- Integrating Centre (where the measured value is compared to a set value)

- Effectors (which can bring about a response)

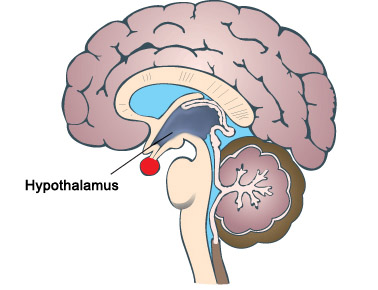

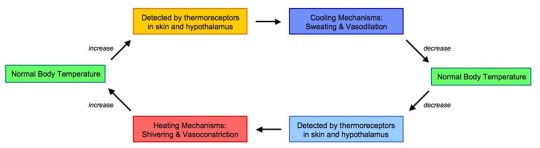

In human thermoregulation, there are two sets of sensors that measure temperature. The skin contains hot and cold receptors which can respond if the skin gets too hot or cold respectively. The temperature of the blood is constantly measured by a second set of thermoreceptors which are found in the hypothalamus in the brain.

The hypothalamus also acts as the integrating centre, collecting information from a variety of sensors and then initiating an appropriate response.

The main effector organ in thermoregulation is the skin.

I have looked at the role of the skin in thermoregulation in an earlier post – click here to be taken to this….

Just check you understand the role of sweating, vasodilation in helping the body lose heat if it gets too hot and vasoconstriction and shivering if it gets to cold. I hope the earlier post will help!

Please add comments/feedback/questions etc using the comment feature at the bottom of this post or tweet me @Paul_Gillam.

Kidney (part II): Grade 9 Understanding of the kidney’s role in osmoregulation 2.76B, 2.78B, 2.79B

The main function of the kidneys is EXCRETION. They remove urea from the blood in a two stage process described in an earlier post, first by filtering the blood under high pressure in the glomerulus and then selectively reabsorbing the useful substances back into the blood as the filtrate passes along the nephron.

But the kidney has an equally important role in HOMEOSTASIS. It actually is the main effector organ for regulating a whole load of variables about the composition of the blood (e.g. blood pH and salt balance) but in this post I want to explain to you how the water balance of the body is regulated and the kidney’s role in this homeostatic system.

Why do you need to regulate the dilution (or water potential) of the blood?

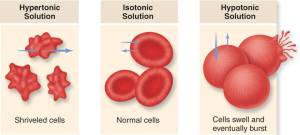

If the blood becomes too dilute, then water will enter all the body cells by osmosis (from a dilute to a more concentrated solution). This net movement into cells would cause them to swell and eventually burst. Bad news all round…

If the blood becomes too concentrated, then water will leave the body cells by osmosis. Cells will shrivel up as they lose water into the blood and this will kill them. Bad news all round….

Remember: a hypertonic solution has a low water potential and is very concentrated. A hypotonic solution has a very high water potential and is very dilute.

The regulation of the water potential of the blood is a very important example of homeostasis in the human. It is often referred to as OSMOREGULATION.

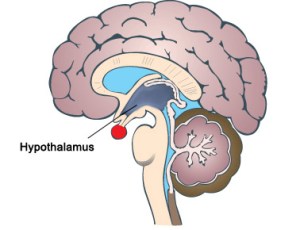

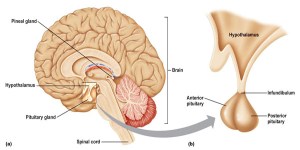

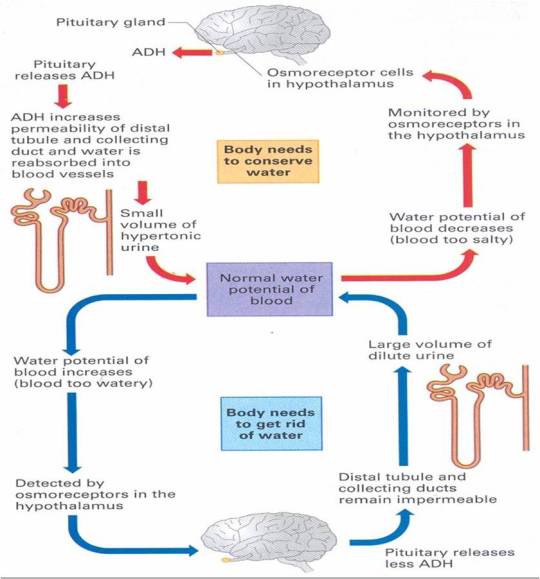

The water potential (dilution) of the blood is measured continuously by a group of neurones in a region of the brain called the hypothalamus.

The hypothalamus is found right next to a very important hormone-secreting gland called the pituitary gland, marked as the red circular structure on the diagram above. When the hypothalamus detects that the blood’s water potential is dropping (i.e. it is getting too concentrated) this causes the posterior lobe of the pituitary gland to start secreting a hormone ADH into the bloodstream.

(You might remember that these brain structures appear elsewhere in the iGCSE specification. The hypothalamus also contains the temperature receptors that measure the temperature of the blood in thermoregulation; the pituitary gland plays a role in the menstrual cycle by producing FSH and LH)

Hormones such as ADH exert their effects elsewhere in the body. The main target tissue for ADH is the collecting duct walls in the kidney. ADH binds to receptors on these cells and makes the wall of the collecting duct much more permeable to water. This means as the urine passes down the collecting duct through the salty medulla of the kidney, lots of water can be reabsorbed into the blood by osmosis. This leaves a small volume of very concentrated urine and water loss is minimised.

ADH is secreted whenever the body is dehydrated. It might be because the person is losing plenty of water in sweating in which case it is vital that the kidney produces as small a volume of urine as is possible.

If you drink a litre of water, what effect will this have on the dilution of the blood: of course it makes the blood more dilute. This will be detected in the hypothalamus by osmoreceptors and they will cause the pituitary gland to stop secreting ADH into the bloodstream. If there is no ADH in the blood, the walls of the collecting duct remain totally impermeable to water. As the dilute urine passes down the collecting duct, no water can be reabsorbed into the blood by osmosis and so a large volume of dilute urine will be produced.

This is another beautiful example of negative feedback in homeostasis.

PMG tip: you can avoid getting confused in the exam about the effect of ADH if you can remember what it stands for. ADH is an acronym for anti-diuretic hormone (ADH). A diuretic is a drug that promotes urine production. They are banned drugs from WADA (World Anti-Doping Agency) since they can be taken as a masking drug to help flush out evidence of illegal drug taking. Shane Warne missed the 2003 cricket World Cup and served a ban for failing a drugs test due to diuretics in his sample.

So an anti-diuretic hormone will reduce urine production. This means it will be secreted when the body is dehydrated as the blood gets too concentrated.

Finally remember that it is not the whole nephron that is affected by ADH, just the collecting ducts and part of the distal convoluted tubules. Most water in the glomerular filtrate is absorbed in the nephron but the collecting duct has a role in “fine-tuning” the volume and dilution of urine.

This is a really important topic to master for an A* in your exam. Examiners seem to like asking questions on ADH and osmoregulation and often these questions are amongst the hardest marks to get in the exam, and so serve as a brilliant discriminator between A and A* candidates. Work hard to master this topic and with a little luck from the question-setters an A* grade is within your grasp……

Kidney (part I): Grade 9 GCSE Understanding of kidney’s role in Excretion 2.72B, 2.73B, 2.74B, 2.75B, 2.76B, 2.77B

Excretion is defined as “the removal of waste molecules that have been produced in metabolism inside cells”. So for example carbon dioxide is a waste product of respiration and is excreted in the lungs.

The liver too produces a waste molecule urea from the breakdown of amino acids. Amino acids and proteins cannot be stored in the body: if you eat more than you use, the excess is broken down to urea. Urea would certainly become toxic if it was allowed to accumulate in the body (patients with no kidney function will die within 3-4 days without treatment) and the organ that is adapted to excrete urea from the blood is the kidney. Kidneys excrete urea by dissolving it in water, together with a few salts to form a liquid called urine.

Don’t confuse urine, the liquid produced in the kidney that is removed from the body, with urea, the nitrogen-containing chemical made in the liver that ends up as one component of urine.

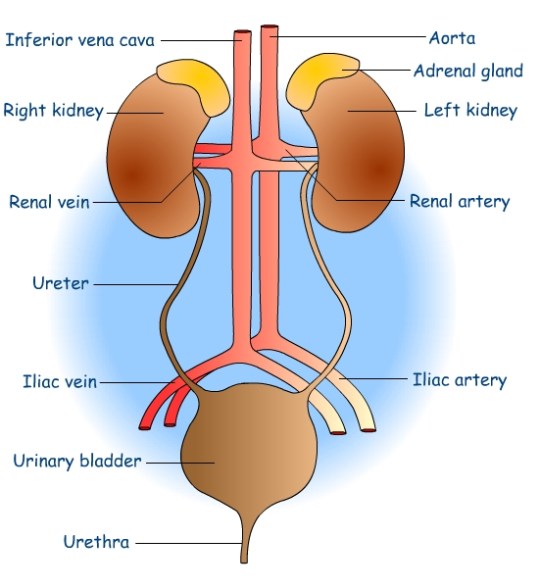

Urine is produced in the kidneys continuously day and night. It travels away from the kidney in a tube called the ureter. Each kidney has a ureter coming out of it, and the two ureters carry the urine to the bladder. The bladder is a muscular storage organ for urine. Urine drains from the bladder through a second tube called the urethra.

Make sure you check your spelling: ureter and urethra are easy to muddle and correct spelling is essential to ensure the meaning is not lost….

How is urine made in the kidney?

Well that’s the big question for this post. How does the kidney start with blood and produce a very different liquid called urine from it….. Urine is basically made of water, dissolved urea and a few salts.

Before I can explain how urine is made, I need to briefly look at the structure of a kidney.

You can see the structure of the kidney on this simple diagram. There are three regions visible in a kidney: an outer cortex, an inner medulla which is often a dark red colour due to the many capillaries it contains, and a space in the centre called the renal pelvis that collects the urine to transfer it into the ureter. Blood enters the kidney through the large renal artery and deoxygenated blood containing less urea leaves the kidney in the renal vein.

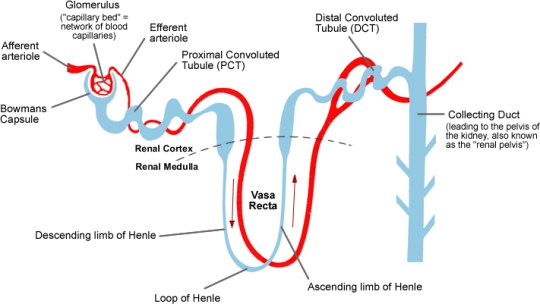

But there is no way from looking at the gross structure of the kidney that you could ever work out how the Dickens it produces urine. This requires careful microscopic examination of the kidney. Each kidney contains about a million tiny microscopic tubules called nephrons. The nephron has an unusual blood supply and an understanding of what happens in different regions of the nephron allows an understanding of how urine is made to be built up.

The nephron is the yellow tubule in the diagram above. It starts in the cortex with a cup-shaped structure called the Bowman’s capsule. This cup contains a tiny knot of capillaries called the glomerulus. The Bowman’s capsule empties into the second region of the nephron which is called the proximal convoluted tubule. The tubule then descends into the medulla and out again in a region called the Loop of Henle. There is then a second convoluted region called the distal convoluted tubule before the nephron empties into a tube called a collecting duct. The collecting ducts carry urine down into the renal pelvis and into the ureter.

Stages in the Production of Urine

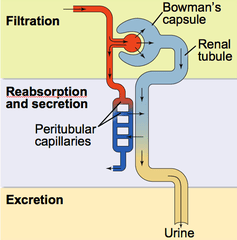

1) Ultrafiltration

Blood is filtered in the kidney under high pressure, a process called ultrafiltration. Filtration is a way of separating a mixture of chemicals based on the size of the particles and this is exactly what happens to the blood in the kidney. Red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets are all too large to cross the filtration barrier. Blood plasma (with the exception of large plasma proteins) is filtered from the blood forming a liquid called glomerular filtrate. The kidneys produce about 180 litres of glomerular filtrate per day.

Ultrafiltration happens in the glomerulus and the glomerular filtrate (GF) passes into the Bowmans capsule. The high pressure is generated by the blood vessel that takes blood into the glomerulus (afferent arteriole) being much wider than the blood vessel that takes blood out of the glomerulus (efferent arteriole). The plasma of blood (minus the large plasma proteins) is squeezed out of the very leaky capillaries in the glomerulus and into the first part of the nephron.

What’s in Glomerular Filtrate?

- water

- glucose

- amino acids

- salts

- urea

As well as containing urea, water and salts, glomerular filtrate also contains many useful molecules for the body (glucose and amino acids for example) so these have to be collected back into the blood in the second stage…..

2) Selective Reabsorption

The useful substances in the glomerular filtrate are reabsorbed back into the blood. This can be by osmosis (for water) or by active transport (glucose and amino acids).

All of the glucose and all of the amino acids in the GF are reabsorbed in the proximal convoluted tubule by active transport. Remember active transport can pump substances against the concentration gradient using energy from respiration. Almost all the water in GF is reabsorbed by osmosis in the proximal tubule too.

So that leaves the question, what is the rest of the nephron doing…?

Well this is where it gets much more complicated…… Extra urea and salts can be secreted into the nephron at certain points along the tubule. The Loop of Henle allows the body to produce a urine that is much more concentrated than the blood plasma. And much of the distal tubules and collecting ducts are used for the second function of the kidney: homeostasis.

But you will have to wait until my next post to find out how the kidney fulfils this crucial second function… Please add comments or questions to this post – I really value your feedback… Tell me what is unclear and do ask questions….

Homeostasis: Grade 9 Understanding for IGCSE Biology 2.81, 2.82

Homeostasis is one of the more difficult topics for students to understand in the iGCSE specification. I have posted already about the skin and its role in thermoregulation so I suggest you read that post again to get the details….

https://pmgbiology.wordpress.com/2014/05/29/skin-a-understanding-for-igcse-biology/

In this post, I am going to try to explain the concept of homeostasis in much more general terms, then in later posts, look at the two examples mentioned in the syllabus. Here goes….

Homeostasis

Homeostasis is one of the life characteristics shared by all organisms. Living things all inhabit a world in which the external environment changes from hour to hour, from day to day, from month to month. Even organisms living in the most stable aquatic environments may be subject to changing oxygen concentrations, changing water pH, changing light intensities and so on. This changing external environment poses a challenge for life since how can life processes operate at optimal levels in all these differing conditions. Life has solved this by allowing organisms to keep their internal environments much more constant than the ever-fluctuating external environment.

A definition to learn:

“Homeostasis is the set of processes occurring in an organism to maintain a constant internal environment”

Examples of Homeostasis in Humans

A whole variety of factors are maintained at constant values in the body by homeostasis. For example (there are many more….):

- Blood pH

- Blood temperature

- Blood dilution

- Blood oxygen concentration

- Blood carbon dioxide concentration

- Blood glucose concentration

- Blood pressure

This introduces the first area of common confusion in students’ exam answers. For some reason many students think that homeostasis is a word for the maintenance of body temperature in humans. I hope you can see it is a much more general term than that.

But…. the systems that maintain a constant body temperature in endothermic animals are one example of homeostasis. In fact this example (thermoregulation) is one of the two from the list above that you need to understand for your exam. The other one you might be asked about is osmoregulation (the maintenance of a constant dilution of the blood).

All homeostatic control systems have some common features. The variable that is going to be regulated needs to be measured somewhere in the body. A change in this variable is called a stimulus and is measured by a cell called a receptor. The measured value needs to be compared with a “set value” and this is done by an integrating centre that then controls an effector. The effector is an organ that can bring about a response. But what kind of response do you want in the process of negative feedback?

A common process involved in homeostasis is negative feedback. This is quite tricky to define but in fact it is a really simple idea……. If you want things to stay the same, any change must be corrected. That’s negative feedback in a nutshell.

For example a school might want students walking round the campus at a sensible speed: not to fast to knock people over, not to slow or people are late for lessons… Imagine a particular group of children who start to run around the place, causing mayhem and injuries to fellow students. Well this will first be detected by the system. There may be a particular teacher who comes out and sees the students running, the school nurse might report an increase in cuts and bruises. However it happens, a change in the system (a stimulus) is detected. There will be an integrating centre in this control system too, probably in the form of a stern deputy head. She will compare the measured speed to her own “set value” of how fast students should move. And she will initiate a response: probably a loud telling off to the entire school in assembly, lots of dire warnings about future conduct and an after school detention for all the rule breakers. The net response of this will be that students will start moving slower around the school…. Eventually of course people will start moving too slowly and will be late for lessons. How do you think the system will react to this new stimulus? This process where the response tends to reduce the stimulus is called negative feedback.

To give you a biological example in thermoregulation, look at the diagram below:

If the body temperature goes up, the system responds by lowering the body temperature.

If the body temperature drops, the system responds by raising body temperature.

Both examples of negative feedback!

The end result of negative feedback is that the value will fluctuate around the set value (see this graph also showing the effect of negative feedback in thermoregulation)

Any questions, problems, queries: please comment using the box below the post or tweet me @Paul_Gillam and I will do my best to help…….

Nerve Cells and Synapses: Grade 9 Understanding for IGCSE Biology 2.88 2.89

There is very little in the iGCSE specification about nerve cells and synapses. This is a shame since neuroscience is going to be one of the massive growth areas in Biology in the 21st century. There is a syllabus point about reflex acs and I draw your attention to this blog post about that: https://pmgbiology.wordpress.com/2014/04/22/a-simple-reflex-arc/

But in this new post I am going to give you a tiny bit more detail about the types of nerve cells (neurones) that you might encounter, together with an explanation about the most important component of the nervous systems: the chemical synapse.

Neurones are the cells in the nervous system that are adapted to send nerve impulses. You won’t fully understand what the nerve impulse is until year 13 but it is correct so that it is a temporary electrical event that can be transmitted over large distances within a cell with no loss of signal strength. The upshot of this is that neurones can be very long indeed…..

There are three basic types of neurone that are grouped according to their function:

Motor neurones (efferent neurones) take nerve impulses from the CNS to skeletal muscle causing it to contract

Sensory neurones (afferent neurones) take nerve impulses from sensory receptors into the CNS

Relay (or sometimes Inter) neurones are found within the CNS and basically link sensory to motor neurones.

These three types of neurone also have different structures although many features are shared….

This is a diagram of a generalised motor neurone: I know it is a motor neurone since the cell body is at one end of the cell. The cell body contains the nucleus, most of the cytoplasm and many organelles. Structures that carry a nerve impulse towards the cell body are called dendrites (if there are lots of them) and a dendron if there is only one. The axon is the long thin projection of the cell that takes the nerve impulse away from the cell body. The axon will finish with a collection of nerve endings or synapses.

Neurones can only send nerve impulses in one direction. In the diagram above these two cells can only send impulses from left to right as shown. This is due to the nature of the junction between the cells, the synapse (see later on….)

The diagram above shows a sensory neurone. You can tell this because it has receptors at one end collecting sensory information to take to the CNS. The position of the cell body is also different in sensory neurones: in all sensory neurones the cell body is off at right angles to the axon/dendron.

You can see from the diagrams that motor and sensory neurones tend to be surrounded by a myelin sheath. Myelin is a type of lipid that acts as an insulator, speeding up the nerve impulse from around 0.5m/s in unmyelinated neurones to about 100 m/s in the fastest myelinated ones. The myelin sheath is made from a whole load of cells (glial cells) but there are gaps between glial cells called nodes of Ranvier. These will become important in Y12/13 when you study how the impulse manages to travel so fast in a myelinated neurone.

Relay neurones, also known as interneurones, have a much simpler structure. They are only found in the CNS, almost always unmyelinated and have their cell body in the centre of the cell.

The diagram above shows the three types of neurone and indeed how they are linked up in a simple reflex arc. The artist hasn’t really shown the interneurone structure very well, but it was the best I could find just now…..

Nerve cells are linked together (and indeed linked to muscle cells) by structures known as synapses. There are a lot of synapses in your nervous system. The human brain contains around 100 billion neurones and each neurone is linked by synapses to around 1000 other cells: a grand total of 100 trillion synapses. 100 000 000 000 000 is a big number.

The big idea with synapses is that the two neurones do not actually touch. There is a tiny gap called the synaptic cleft between the cells. The nerve impulse does not cross this tiny gap as an electrical event but instead there are chemicals called neurotransmitters that diffuse across the synaptic cleft.

The nerve impulse arrives at the axon terminal of the presynaptic neurone. Inside this swelling are thousands of tiny membrane packets called vesicles, each one packed with a million or so molecules of neurotransmitter. When the impulse arrives at the terminal, a few hundred of these vesicles are stimulated to move towards and then fuse with the cell membrane, releasing the neurotransmitter into the synaptic cleft. The neurotransmitter will diffuse rapidly across the gap and when it reaches the post-synaptic membrane, it binds to specific receptor molecules embedded in the post-synaptic membrane. The binding of the neurotransmitter to the receptor often causes a new nerve impulse to form in the post-synaptic cell.

These chemical synapses are really beautiful things. They ensure the nerve impulse can only cross the synapse in one direction (can you see why?) and also they are infinitely flexible. They can be strengthened and weakened, their effects can be added together and when this is all put together, complex behaviour can emerge. I am going to exhibit some complex behaviour now by choosing to take my dogs for a walk… And it all happened due to synapses in my brain!

Adrenaline: Grade 9 Understanding for IGCSE Biology 2.94

Adrenaline is a hormone produced in the adrenal glands which are found on top of the kidneys in the abdomen.

A hormone is “a chemical released by a specialised gland called an endocrine gland into the bloodstream. The hormone travels around the body in the blood plasma and then causes an effect elsewhere in the body by binding to receptors found on certain target cells”.

You should know some other examples of hormones – testosterone, oestrogen, progesterone, ADH – to name a few. Please learn this definition too: it would be wonderful if you got a 3 mark question asking you to define a hormone….

There are many cells in the body that contain receptors for adrenaline. This allows the hormone to exert an effect on a wide variety of tissues. For example there are adrenaline receptors in the pacemaker of the heart and adrenaline will cause the heart to beat faster (more beats per minute) and also with more force.

When is adrenaline released by the adrenal glands into the blood?

Adrenaline is secreted into the blood in times of danger or stress. It prepares the body to either run away from the danger or indeed to battle against it. For this reason, adrenaline is often described as a “fight or flight” hormone.

What are some of the effects of adrenaline?

Target Tissue Effect

Heart Increase in heart rate, increase in cardiac output

Lungs Bronchioles dilate (widen)

Muscles Arteries in muscle dilate to allow more blood to flow to muscles

Skin/Digestive system Arteries in skin/digestive system constrict so less blood flows

Liver Liver breaks down glycogen into glucose to raise blood glucose conc.

Iris Radial muscles in iris contract causing pupil dilation

The overall effect is that the skeletal muscles are supplied with more oxygen and more glucose so they can respire aerobically. This allows the muscle to contract more efficiently.