Category: IGCSE Biology posts

The Human Alimentary canal: Grade 9 Understanding for IGCSE Biology 2.27

A human body is in many ways rather like a packet of polo mints. These are famous mints in the UK for having a hole in the middle. Our body is divided into segments (rather like the packet of polos) and we have a tube that runs through the middle of us. This tube is called the Alimentary Canal (or Gut) and it’s function in the body is the digestion and absorption of food molecules (see later post on “Stages of Processing Food”)

The Alimentary Canal is divided into specialised regions, each with its own particular range of functions to do with the processing of food. You are required to understand a little about some of these organs and their functions.

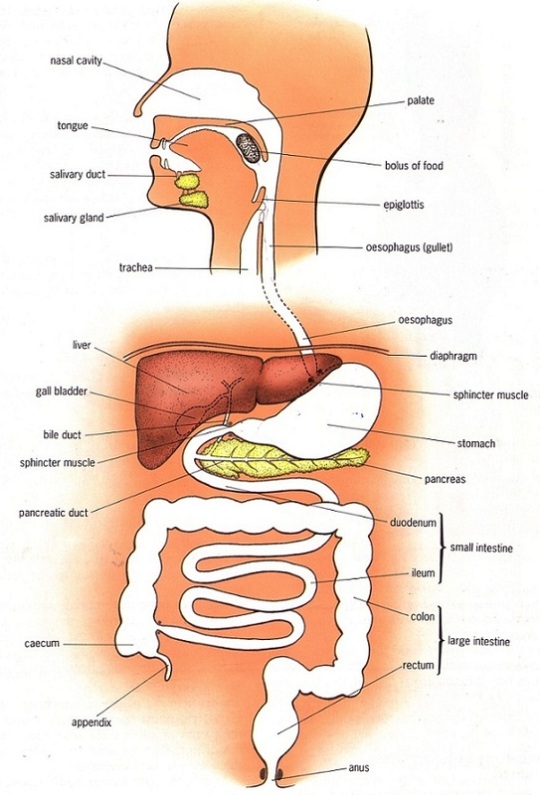

The first thing is to make sure you can label a diagram of the human digestive system such as the one shown above. Check that you could accurately identify the following structures:

mouth, tongue, teeth, salivary glands, oesophagus, stomach, liver, gall bladder, bile duct, pancreas, pancreatic duct, duodenum, ileum, colon, appendix, rectum, anus

Here is a good diagram to use to check your labelling of the human digestive system

Functions

1 Mouth

The mouth is actually the name for the opening at the top of the alimentary canal rather than the chamber behind. If you want to be really precise, you should call this chamber containing the tongue and teeth by its proper name, the buccal cavity. The mouth is the opening that allows an animal to ingest food. In the buccal cavity, the teeth can chop up the food into smaller pieces and the tongue can move the food into a ball (bolus) for swallowing. The food is tasted in the buccal cavity and there are many chemoreceptors on the tongue and in the nasal cavity that perform this function. There are three sets of salivary glands around the buccal cavity and these secrete a watery liquid, saliva to mix with the ingested food. Saliva is alkaline to help protect the tooth enamel from acidic decay by bacteria but also contains a digestive enzyme, salivary amylase that begins the process of digestion of starch in the mouth. Salivary amylase catalyses the hydrolysis reaction in which starch, a polysaccharide is digested into the disaccharide maltose.

2 Oesophagus

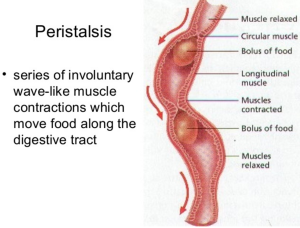

The oesophagus is the tube that carries the ball of food from the back of the throat through the thorax and down into the stomach. The Alimentary canal has layers of muscle in its wall throughout its entire length. These layers of smooth muscle can contract and relax in an antagonistic fashion to push the bolus along the tube. There are two main types of smooth muscle in the wall of the Alimentary canal – circular fibres are arranged around the circumference of the tube and longitudinal fibres are arranged along the length of the tube. These waves of alternate contraction and relaxation are called peristalsis.

3 Stomach

The stomach is a muscular storage organ that keeps food in it for around 3-4 hours before squirting it out in small amounts into the duodenum. The muscle layers in the stomach wall churn the food and mix it with the secretions from the stomach lining. These secretions are called gastric juice and contain a mixture of hydrochloric acid, mucus and a digestive enzyme pepsin. The acid makes the gastric juice overall very acidic, around pH 1.5. This acidity forms part of the non-specific defences of the body against bacteria as the extreme pH kills almost all bacteria in the food. The mucus is important as it protects the cells lining the stomach from the acidity. Pepsin is a digestive enzyme that starts the digestion of protein. It catalyses a hydrolysis reaction in which proteins are broken down into smaller molecules called polypeptides. Pepsin is an unusual enzyme in that it has an optimum pH of around 1.5.

4 Small Intestine

I will write a whole post on the small intestine later this week as there is plenty for you to understand about this part of the alimentary canal. All I will say here is that it is divided into the duodenum which is where almost all the digestion reactions take place and the ileum which is adapted for efficient absorption of the products of digestion into the blood. (see post later in the week if you want to find out more….)

5 Large Intestine

The majority of the large intestine is made up of an organ called the colon. The colon has a variety of functions. It is where water from all the various secretions is reabsorbed back into the blood, thus producing a solid waste called faeces. (Water that you drink tends to be absorbed through the stomach lining much earlier in the alimentary canal) There are also a few mineral salts and vitamins absorbed into the bloodstream in the colon. The colon is also home to a varied population of bacteria, the so called gut flora. Faeces is stored in the final part of the large intestine that is called the rectum.

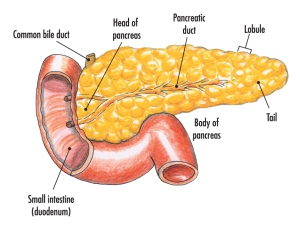

6 Pancreas

The pancreas is not part of the alimentary canal (although I am not sure the person who wrote the specification appreciated that….) It is an example of what is called an accessory organ for the digestive system. The pancreas is a really interesting organ as it contains different cell types that carry out two completely separate functions. The majority of the cells in the pancreas secrete a whole load of digestive enzymes into an alkaline secretion called pancreatic juice. There is a tube called the pancreatic duct that carries the pancreatic juice and empties it into the duodenum where it can mix with the acidic chyme coming out of the stomach.

There are small clusters of a different kind of cell found in the pancreas. These are the islets of Langerhans that secrete the hormones insulin and glucagon into the bloodstream. These two pancreatic hormones together regulate the blood glucose concentration.

Cloning in Mammals: Grade 9 Understanding for IGCSE Biology 5.19B 5.20B

The most famous sheep in the world currently resides in a display cabinet at the National Museum of Scotland. Dolly became internationally famous in 1996 as the first animal cloned using a nucleus from an adult animal. Cloning experiments had been going on since the 1950s but previous to Dolly only embryonic cells could be used as the source of the donor DNA.

So how was Dolly the sheep made? She was a clone of an adult sheep and because the cell used to provide the nucleus from this adult donor was from an udder cell, the researchers decided to call her Dolly after the American singer Dolly Parton. (No further explanation required but the photo of Dolly Parton below might give you a clue….)

The technique used to make Dolly was given the catchy title somatic cell nuclear transfer. A nucleus was taken from an adult cell in the udder (somatic cells are any cells whose DNA will not be inherited to the next generation) and this was fused with an enucleated egg cell (an egg cell which has had its nucleus removed). This cell contains the nuclear DNA from the adult donor but will divide and develop into an embryo. The embryo can then be implanted into the uterus of a surrogate sheep for it to complete its development.

You can see that three sheep (all female in this instance) were used to produce Dolly. The tissue cell donor provided the udder cell and all the nuclear DNA for the cloned sheep. A second sheep provided the egg cell which was then enucleated. And finally a third sheep acted as a surrogate mother and so provided the uterus in which Dolly would develop to birth. The researchers cleverly used three breeds of sheep so they could check that the various processes all worked correctly.

Potential Applications of Cloned transgenic animals

If researchers combine this “Dolly technology” with the ability to genetically modify the embryonic cells produced, then it will be possible in the future to produce cloned transgenic animals. A transgenic organism is one that contains DNA from more than one species.

One potential application is that cloned animals could be genetically-modified to produce human antibodies. These polyclonal antibodies are useful in treating various medical conditions (see the New Scientist article below)

https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn2658-cloned-cows-produce-human-antibodies/

A second potential application could be to use cloned animals that have been genetically modified as potential donors for medical organ transplantation in humans. You all know that in most developed countries there is a shortage of organs for transplants to patients who need them. Added to this is the fact that the recipient’s immune system will recognise the donated organ as ‘foreign’ and so mount an immune response against it. This rejection can be combatted with immunosuppressant drugs but these have nasty side effects. Imagine if a replacement organ could be grown in a cloned animal for you, and this organ could express your own surface protein markers on its cell membranes. No problem with shortage of donors, no problems of rejection! Pigs are being used in research at the moment as pig abdominal organs are very similar in size to humans…. Here is a newspaper article looking at another possible way cloning technology could be applied to organ transplantation.

Micropropagation in Plants: Grade 9 understanding for iGCSE Biology 5.17B 5.18B

Cloning is the process of producing many genetically identical organisms. I am going to write two posts on cloning: this one on cloning plants and then later, a second post on cloning animals. As this blog grows to cover the entire iGCSE specification, it does mean that I will have to blog on some of the less exciting (to me at least) topics in Biology. Micropropagation of plants does not get to me in the same way as other topics, so I apolgise in advance if this post is rather dull……

Cloning in Plants

Plants are relatively straightforward to clone, at least compared to animals. Their bodies are made of fewer tissues and the genetic developmental program in plants is simple enough that many cells retain their totipotency into maturity. The process of micropropagation, also known as tissue culture, is the main mechanism for cloning a plant. Small samples from an adult plant are cut out. These tiny explants can be sterilised in dilute bleach to kill surface bacteria and fungi, then grown in a suitable culture medium. The explants divide by mitosis and grow but if the chemicals in the growth medium are correct, they will also start to differentiate into roots, shoots and leaves.

The experiment that you will have done on this in school involves cloning cauliflower plants. A cauliflower can be divided up into many thousands of explants and these are cultured on Murashiga and Skoog growth medium. This M&S medium contains the minerals, sugars and amino acids needed to grow but it also contains plant growth substances such as auxins and cytokinins. These growth substances can switch on root and leaf development and so rather than just producing a larger ball of cells called a callus, the explants will develop roots and shoots so they can be planted into compost. Seeing as the only cell division in this whole process is mitosis, the plantlets will all form a clone of the original parent plant.

In practice what tends to happen in these experiments is that the surface sterilisation does not work fully and so students end up growing a boiling tube full of bacteria and fungi.

Micropropagation does have commercial applications as it can produce large quantities of genetically identical plants. This allows the plant breeder to produce plants all year round without needing pollinating insects. The breeder can also guarantee the exact genetic make up of every plant as they are all a clone. Sexual reproduction of course introduces genetic variation into the offspring and although this might be advantageous to plants in the wild, for a plant breeder it is unwelcome as many of the offspring may not grow as well or be as tasty to eat as their parent. So if she starts with a plant with desirable features (good tasting fruit/disease resistance/easy to grow etc.) then every single plant in the clone will have the same desirable characteristics. Banana plants can be produced commercially by micropropagation.

If you find micropropagation interesting, you are a better biologist than me. But I hope this post proves useful if not entertaining….

Variation: Grade 9 Understanding for IGCSE Biology 3.33

Variation within a population is a critical and required component for natural selection. If you have understood all the work on DNA, chromosomes and Mendelian genetics, you should now have a good understanding of where the genetic causes of this variation comes from. But remember that variation can also be caused by the environment. Indeed all variations in reality come from an interplay between genetic and environmental factors. Genes by themselves cannot cause variation as without the environment of a cell to produce the protein, genes alone cannot affect the phenotype.

Genetic causes of variation

Sexual reproduction is the key to genetic variation in a population. Meiosis produces gametes that are haploid and genetically different from each other. The gametes may have a different combination of randomly “shuffled” chromosomes. Crossing over in meiosis also allows alleles that would not otherwise be combined in a gamete. So there are massive genetic differences between one gamete and the next. And then there is random fertilisation so that any one male gamete is equally likely to fuse with any female gamete. Random fertilisation (of gametes that meiosis has made genetically different to each other) is the key to genetic variation in a population.

A final cause of genetic variation has nothing to do with sexual reproduction and is mutation. DNA replication is not 100% accurate – the enzymes in eukaryotes make one error every billion base-pairs. These mutations are random and can lead to new alleles appearing in a population. Chromosomal mutations can also occur where chromosomes do not separate properly in meiosis or parts of a chromosome break off and re-join somewhere else….

Environmental causes of variation

Some of the differences seen in populations are due not to differences in genes but due to the differing environments in which an organism lives. Peas which have inherited two copies of the T allele (for tallness) will never grow tall unless they are planted in well-watered soil and given access to sunlight. You would never be a school teacher as a career without understanding that the environment a brain develops in can affect a person’s outcomes. Environment is as important as genes in many variations in the human population, in particular to do with health and disease. This is why so much emphasis for health for example is placed on promoting balanced diets, altering smoking habits, and moderating alcohol consumption.

Genes and Environment always interact to determine Phenotype

Don’t allow yourself to fall into the lazy thinking of the “nature-nurture” debate. It is lazy thinking because the debate is a nonsense. Nothing is either determined by your genes or your environment – it is always both. So when you read of a ‘gene for obesity’ or a ‘gene for domestic violence’ treat with extreme caution (and switch newspapers……) If you read that playing violent computer games causes violent behaviour in humans, treat with caution. None of these variations in a population will be just due to genes, none will be just do to the environment. It will always be some complex interaction between the two.

Cell Division part 3: Grade 9 Understanding of Meiosis for IGCSE 3.30

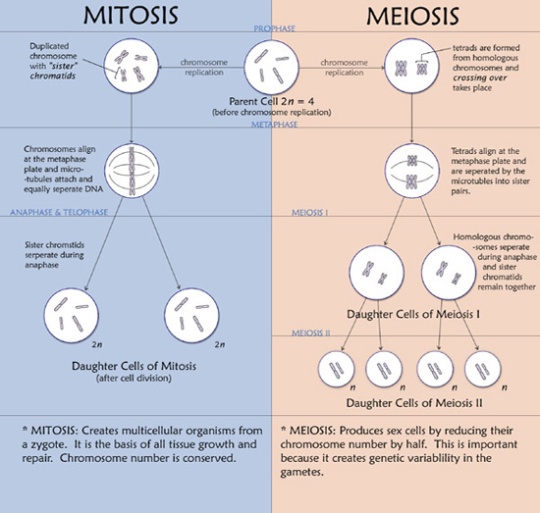

In sexually reproducing organisms two types of cell division are needed. One is for the processes of growth, repair and asexual reproduction and it is called mitosis. Mitosis produces daughter cells that are diploid and genetically identical to the parent cell.

But when the organism wants to make gametes a different mechanism is needed. Gametes are not diploid like all the other body cells, but instead they only have one member of each homologous pair of chromosomes. In order to make a haploid daughter cell, a second type of cell division, meiosis, is needed.

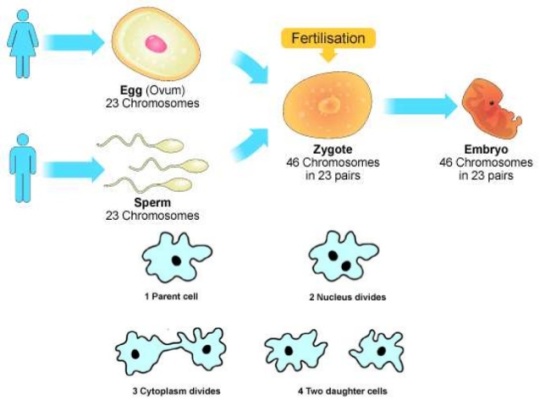

You can see in the diagram above some of the key differences between mitosis and meiosis. Both start with diploid cells (2n) but whereas mitosis involves one round of division and produces two identical diploid daughter cells, meiosis is different. Meiosis has two rounds of division, called Meiosis I and Meiosis II. This results in four daughter cells and you can see that they are all haploid (n) cells. These cells develop into gametes (sperm and egg cells in humans) and so when they fuse together in fertilisation, the diploid number is restored.

Gametes are all genetically different to each other

Meiosis does not just produce haploid daughter cells. It also introduces genetic variation into the daughter cells so each is genetically unique. This means that random fertilisation will produce offspring that are all genetically different to either parent. How does this genetic variation in gametes come about?

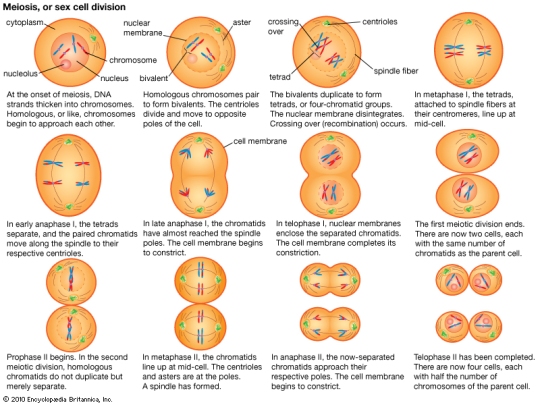

Well to answer that, you need to understand a little bit more about how the chromosomes behave during meiosis. I am not going to talk through all the various stages of meiosis (life is too short and you can read the diagram below) but there is a key event that happens in meiosis that never happens in mitosis…..

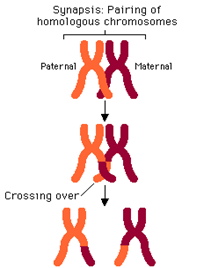

It happens in prophase of the first meiotic division and is called synapsis. As the nuclear membrane is degenerating, the two members of a homologous pair of chromosomes line up alongside each other to form a structure called a bivalent (or tetrad)

In the first meiotic division, the two members of the homologous pair are pulled apart and separated. Because these bivalents attach and assort independently of each other, this means that this random assortment can produce many different gametes. A human cell with 23 pairs of chromosomes can produce 2^23 possible gametes just by random assortment.

But there is a second process called crossing over that happens during prophase 1 when the bivalents are formed. As you can see in the diagrams, small sections of chromatid can be swapped between the chromatids of one chromosome and with its homologous partner. This ensures that when the individual chromatids are separated in meiosis 2, each is different to each other. This multiplies up the genetic variation by several orders of magnitude. (see diagram below)

Now that is more detailed than you will need in an iGCSE exam, but it is good to understand where the genetic variation in gametes comes from. Let’s finish with something more simple – the differences between mitosis and meiosis.

One final point: please learn the spellings of these two types of cell division. Spelling is only penalised in exams when the meaning is lost and any intermediate spelling (e.g. meitosis or miosis) has no meaning! So if you are one of those people who finds spelling difficult, find a way of learning mitosis (produces identical diploid daughter cells and is used in growth) compared to meiosis (produces genetically different haploid cells and is used to make gametes)

Cell Division part 2: Grade 9 Understanding of Mitosis for IGCSE 3.28 3.29

I thought I would make a video to explain the details of mitosis rather than typing up a blog post.

I would welcome any feedback on either of these videos. Do you find them useful? Do you prefer written blog posts? Leave a comment below if you want to let me know…..

Cell division video: a revision video for DNA structure and chromosomes

This is a summary video that might help those of you still struggling to get to grips with chromosomes and genes. I apologise for the terribly amateur production values on the video but hope the biological content at least might be useful….

Cell Division part I: Grade 9 Understanding for IGCSE 3.15, 3.28, 3.29

At the beginning of March each year, I get my Y11 classes to draw up a list of topics they want to go through again in revision. Cell Division is always there and it is not difficult to see why. Mitosis doesn’t make any sense unless you understand the concept of homologous pairs of chromosomes and I think you already know that very few iGCSE students do…… (Please see the various posts and videos on the blog on this topic before attempting to understand mitosis)

But there is actually very little to fear in the topic of cell division. If your teacher has told you about the various stages of mitosis that’s fine but you will not be asked to recall them in the exam, at least not if you are studying EdExcel iGCSE. So in this post I am going to try to focus on the key bits of understanding you need rather than bombarding you with unnecessary details.

1 Chromosomes come in pairs

This is the main idea you need before you start. In almost all sexually-reproducing organisms the cells are DIPLOID. This means that however many different sized chromosomes they have, in each cell there will be pairs of chromosomes (called homologous pairs)

So human cells contain 23 pairs of chromosomes (46 in total)

Remember that the number 46 only applies to humans. Other species have very different numbers of chromosomes in each cell (see table below)

So doves have 8 pairs of chromosomes, dogs have 39 pairs of chromosomes, rats 21 pairs of chromosomes. The important point is not how many pairs each organism has but that they all have chromosomes that come in pairs!

The chromosomes any individual possesses is determined at the moment of fertilisation. Sperm and Egg cells (gametes) do not have pairs of chromosomes. They are the only cells in the body that are not diploid. Gametes only have one member of each pair of chromosomes. Cells which only have one member of each pair of chromosomes are called HAPLOID cells.

So every cell in the body is diploid and genetically identical apart from the gametes which are haploid.

2 Organisms that reproduce sexually need two different types of cell division

The fertilised egg (zygote) is a diploid cell. It has pairs of chromosomes that originate one from each parent via the gametes. Every cell division in growth and development of the embryo and foetus until birth, every cell division in growth and repair after birth always produces two genetically identical and diploid cells from the one original cell. This cell division that produces genetically identical diploid cells is called Mitosis.

Gametes (sperm and egg cells) need to be made by a different process. If gametes were diploid then there would be a doubling of the chromosome number every generation and that clearly wouldn’t do. So a different way of dividing the nucleus has evolved. It doesn’t produce genetically identical diploid cells but produces gametes that are haploid and genetically unique. This process is called Meiosis and is only used in the production of gametes.

3 Mitosis is involved in growth, repair, asexual reproduction and cloning

Any process in the body in which the outcome required is the production of genetically identical diploid cells will use mitosis. (It is not too complicated an idea to see that if you don’t need to make gametes and fuse them together in fertilisation, you can just copy cells by mitosis over and over again. All the daughter cells will be exact copies of each other and diploid.

Now I know this post is not going to satisfy everyone. I know some of you will want to read about the cell cycle, prophase, metaphase, centrioles, spindle fibres and the condensation of chromosomes, chromatids being pulled apart etc. etc.) And just for you, I will write a post later today on the details of Mitosis….. But please remember that if you are using the blog to revise for exams, none of this second post is necessary and none of it will be tested in the Edexcel iGCSE paper. If you are doing revision, focus on the key understanding ideas discussed above. And as always, please leave a reply below to ask questions, comment or leave feedback – all comments welcome!

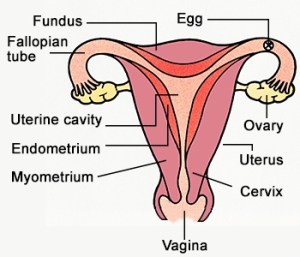

Female Reproductive System: Grade 9 Understanding for IGCSE Biology 3.8

The human male and female reproductive systems are made from the same embryonic cells and are perhaps more similar in structure and function than is first apparent. There are two ovaries protected within the pelvic cavity. The ovary is the site of egg cell production. The egg cell is the female gamete and is haploid – it has only one chromosome from each homologous pair. The ovaries are also endocrine organs that produce the female sex hormones oestrogen and progesterone.

[Indeed differences between the gametes is the essential difference between male and female organisms. Females are always individuals who produce a small number of large, often immobile gametes. You can easily remember this: female – few, fixed, fat. Males are organisms that produce large numbers of small, motile games. Male – many, mini, motile.]

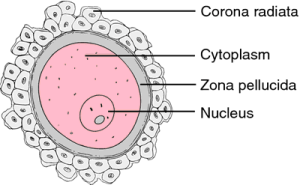

This diagram shows the human egg cell after it has been released from the ovary into the Fallopian tubes (or oviduct). The egg cell is coloured pink in the diagram above (if you are being picky it is not really an egg but a cell called a secondary oocyte but I won’t stress over this now…) The egg cell is surrounded by a thick jelly-like layer called the zona pellucida and then by a whole cluster of mother’s cells from her ovary – the corona radiata. The big idea to remember is that the egg cell is very large compared to sperm cells: it is one of the largest cells in humans with a diameter of about 500 micrometers.

The Fallopian tubes carry the egg down towards the uterus. The lining of the Fallopian tubes is covered in a ciliated epithelium. The cilia waft to generate a current that helps move the egg down towards the uterus. Sperm cells have to swim against this current to reach the egg in the tubes. The Fallopian tube is the usual site for fertilisation to occur.

Once fertilisation has occurred, the newly formed zygote divides over and over again by mitosis to form a ball of cells called an embryo. The embryo continues its journey down the Fallopian tube until it reaches the uterus. The uterus (womb) is a muscular organ with a thickened and blood-rich lining called the endometrium. Implantation occurs when the embryo attaches to the endometrium and over time, a placenta forms. The embryo develops into a foetus and remains in the uterus for 9 months.

The cervix is a narrow opening between the uterus and the vagina. It holds the developing foetus in the uterus during pregnancy but dilates (widens) at birth to form part of the birth canal. The vagina is the organ into which sperm are deposited from the man’s penis during sexual intercourse. The lining of the vagina is acidic to protect against bacterial pathogens and the sperm cells released into the vagina quickly start to swim away from the acidity in grooves in the lining. These grooves lead to the cervix and hence into the uterus.

Last few IGCSE Biology blog posts on their way…

I am very close to having a comprehensive coverage of the EdExcel iGCSE Biology specification on my site. These are the last few topics I need to address:

- Female Reproductive system

- Mineral Ions in Plants

- Human diet

- The Digestive System in Mammals

- Small Intestine

- Comparison between Sexual and Asexual reproduction

- Cell Division

- Use of Quadrats

- Air pollution and Climate Change

- Deforestation

- Microorganisms and Food Production

- Growing Crop plants

- Fish farming

- Cloning in Plants

- Cloning in Animals

I hope that I can write the last few posts between now and Christmas. Then I can focus again on the common areas of confusion and poor understanding in the run up to iGCSE papers in summer 2016.