Category: Section 3: Reproduction and Inheritance

DNA structure and function – IGCSE Grade 9 Understanding 3.16B

I have been working today on making a video to explain DNA structure, chromosomes and cell division to post on YouTube. This has proved harder than I anticipated (not just because I look ridiculous and keep stuttering….) but I hope there may be something for you by lunchtime tomorrow….

So I will have to resort to the more old-fashioned medium of the blog. (The times they are a’changing)

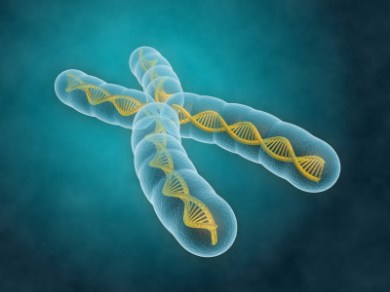

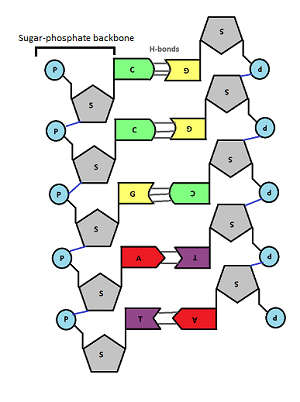

Firstly DNA is from the family of molecules called Nucleic Acids. These are examples of biological polymers (macromolecules) and you should know that a polymer is a large molecule made of a chain of repeating subunits.

The monomers that make up a DNA molecule are called nucleotides. A single nucleotide is made up of a phosphate group attached to the sugar, deoxyribose which in turn is attached to a nitrogenous (nitrogen-containing) base.

Every nucleotide in DNA has the same phosphate group, the same sugar (deoxyribose) but there are four alternative bases in DNA nucleotides. You don’t need to worry about the structure of these four bases but you do need to know their names: Adenine, Guanine, Cytosine and Thymine.

Now the next idea is that a single DNA molecule is actually made up of two chains of nucleotides joined together. These two polynucleotide chains line up alongside one another and are held together by hydrogen bonds between the pairs of bases in the middle of the molecule. There are two antiparallel sugar-phosophate backbones on the outside and the pairs of bases in the middle. You can see that the bases always pair together in a predictable way. A pairs with T (joined by two hydrogen bonds) and C pairs with G (joined by three hydrogen bonds)

Can you see why the two strands that make up the DNA molecule are described as being antiparallel?

There are only two more things to appreciate about the structure of the molecule DNA:

Firstly it is appreciating how long the actual DNA molecule might be. The diagram above shows a structure 5 base pairs in length. The DNA molecules in the nuclei of your cells might be hundreds of millions of base pairs in length. If you look at the sum total in a single human nucleus there are DNA molecules 3 billion base pairs long – a molecule that if allowed to line up in a straight line would extend to around 2 metres in length.

And finally the fact about the structure of DNA that everyone remembers – it is a double helix. The two sugar-phosphate backbones do not run in a straight line as in the diagram above but coil around each other into the infamous double helix.

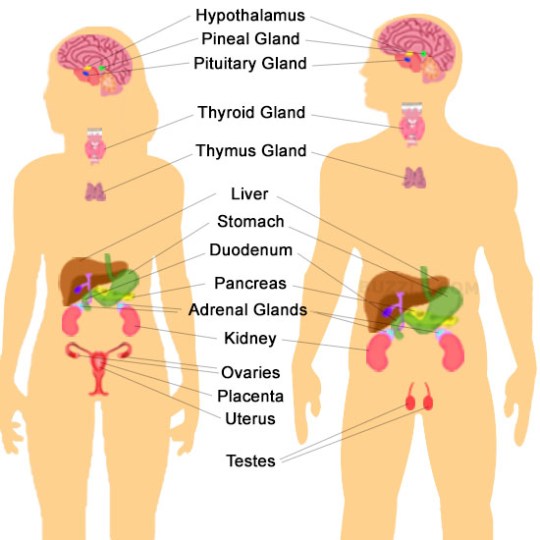

Hormones: Grade 9 Understanding for IGCSE Biology 2.94 2.95B

Hormones are defined as “chemicals produced in endocrine glands that are secreted into the bloodstream and cause an effect on target tissues elsewhere in the body”. They play a wide variety of roles in the healthy functioning and development of the body.

The iGCSE specification only really mentions a small number of hormones so these are the ones I will focus on in this post.

ADH (anti-diuretic hormone) (Separate Biologists only – not Combined Science)

ADH is secreted into the blood by an endocrine gland at the base of the brain called the Pituitary Gland. The stimulus for the release of ADH into the blood comes from the hypothalamus (a region of brain right next to the pituitary gland) when it detects that the blood plasma is becoming too concentrated. This might be caused by the body becoming dehydrated due to sweating. ADH travels round the body in the blood until it reaches its target tissue which are the cells that line the collecting ducts in the nephrons in the kidney. ADH increases the permeability of the connecting duct walls to water, thus meaning more water is reabsorbed by osmosis from the urine in the collecting duct and back into the blood. This results in a small volume of concentrated urine being produced.

Adrenaline

Adrenaline is secreted into the blood by the adrenal glands in situations of danger or stress.. The adrenals are found just above the two kidneys on the back of the body wall. Adrenaline secretion is controlled by nerve cells that come from the central nervous system. Adrenaline is often described as the “fight or flight” hormone as its effects are to prepare the body to defend itself or run away from danger. There are receptors for adrenaline in many target tissues in the body but some of the most significant effects of adrenaline are:

- affects the pacemaker cells in the heart causing an increase in heart rate

- shifts the pattern of blood flow into muscles, skin and away from the intestines and other internal organs

- decreases peristalsis in the gut

- causes pupils to dilate in the eye

- increases breathing rate in the lungs

- promotes the passing of urine from the bladder

Insulin

Insulin is a hormone made in the islets of Langerhans in the pancreas. It plays a vital role in the homeostatic control of the blood sugar concentration. The pancreas will secrete insulin into the blood when the blood glucose concentration gets too high. There are many cells in the body with insulin receptors but the main target tissue for insulin is the liver.

Insulin causes the liver (and muscle) cells to take glucose out of the blood and convert it into the storage polysaccharide glycogen. This results in a lowering of the blood glucose concentration: a good example of the importance of the principle of negative feedback in homeostasis

Testosterone

Testosterone is a steroid hormone made by cells in the testes of males. It is the main hormone of puberty in males resulting in the growth of the reproductive organs at puberty as well as the secondary sexual characteristics (pitch of voice lowering, muscle growth stimulated, body hair grows etc.)

Oestrogen

Oestrogen is a steroid hormone made by the cells in the ovary that surround the developing egg cell in the first half of the menstrual cycle. In puberty it causes the development of the female secondary sexual characteristics (breast growth, change in body shape, pubic hair etc.) but in the menstrual cycle, oestrogen has a variety of important effects. It stimulates the rebuilding of the uterine endometrium (or lining) to prepare the uterus for the implantation of an embryo. Oestrogen also affects the pituitary gland and can cause the spike in LH concentrations that trigger ovulation on day 14 of the cycle.

Progesterone

Progesterone is also made in the ovary but at a different time in the menstrual cycle. It is secreted by cells in the corpus luteum, a structure found from day 14 onwards after the egg has been released in ovulation. Progesterone has two main target tissues: it maintains the thickened lining of the endometrium in the uterus ready for implantation. Progesterone also causes the pituitary gland to stop secreting the hormones FSH and LH so a new cycle is never started. It is for this reason that progesterone can be used in women as a contraceptive pill.

FSH (Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (Separate Biologists only – not Combined Science)

FSH is a hormone released by the pituitary gland underneath the brain. The target tissues for FSH are in the testis (males) and ovaries (females). In males FSH plays a role in the growth of the testes allowing sperm production to start. In females, FSH is the hormone released at the start of the menstrual cycle that causes one of the immature egg cells in an ovary to grow, develop and so become surrounded by follicle cells prior to ovulation.

LH (Luteinising Hormone) (Separate Biologists only – not Combined Science)

LH is a second reproductive hormone released by the pituitary gland into the bloodstream. In males, it stimulates the production of testosterone in the testes. In females, it is released only on days 13 and 14 of the menstrual cycle and it is the hormone that triggers ovulation.

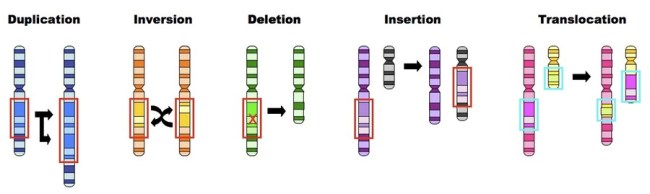

Mutation – Grade 9 Understanding for IGCSE Biology 3.34 3.37B

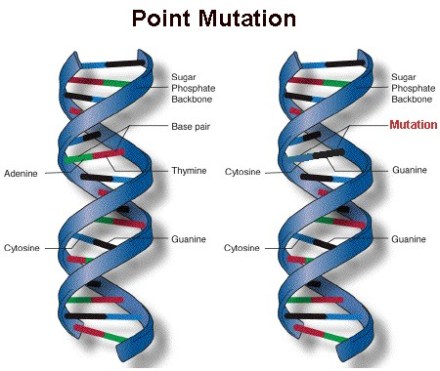

Mutations are changes in the DNA content of a cell. There are various ways the DNA of a cell could change and so mutations tend to be grouped into two main categories: chromosomal mutations and gene mutations.

Chromosomal mutation

This is a change in the number or length/arrangement of the chromosomes in the nucleus. For example, people with Down’s syndrome have an extra copy of chromosome 21 giving them three chromosome 21s as opposed to the normal two.

(How many chromosomes in total will a person with Down’s syndrome have in each cell?)

Chromosomal mutations are often found in tumour cells and so play a critical role in the development of various cancers.

Sometimes the number of chromosomes in a cell stays the same, but sections are deleted, duplicated or break off from one chromosome to attach elsewhere. If this happens, this too would be classed as a chromosomal mutation.

Gene mutation

Gene mutations happen to change the sequence of base pairs that make up a single gene. As you all know, the sequence of base pairs in a gene is a code that tells the cell the sequence of amino acids to be joined together to make a protein. A gene then is the sequence of DNA that codes for a single protein. If you alter the sequence of base pairs in the DNA by adding extra ones in, or deleting some or inverting them, this will alter the protein produced.

A point mutation is a change to just one base within the gene – it occurs at a single point on the DNA molecule.

Mutations can happen at any time and occur randomly whenever the DNA is replicated. But there are certain things that can increase the rate of mutation and so make harmful mutations more likely. A mutagen is an agent that increases the chance of a mutation occurring.

a) Radiation can act as a mutagen

Some parts of the electromagnetic spectrum can cause mutations when they hit DNA molecules or chromosomes. This is called ionising radiation and includes gamma rays, X rays and ultraviolet. You probably know that the dentist goes out of the room whenever they take an X ray to protect themselves from repeated exposure to X rays and you all certainly know of the link between UV exposure and incidence of skin cancer.

b) There are chemical mutagens as well

Some chemicals can make the rate of mutation increase. These are called chemical mutagens and a good example is the tar in tobacco smoke. Tar can cause cancers to form wherever the cigarette smoke comes into contact with cells and this is because tar is a mutagen. It makes mutations in the DNA much more likely and mutations are needed to turn a healthy cell into a cancer cell.

Role of the Amnion – Grade 9 Understanding for IGCSE Biology 3.12

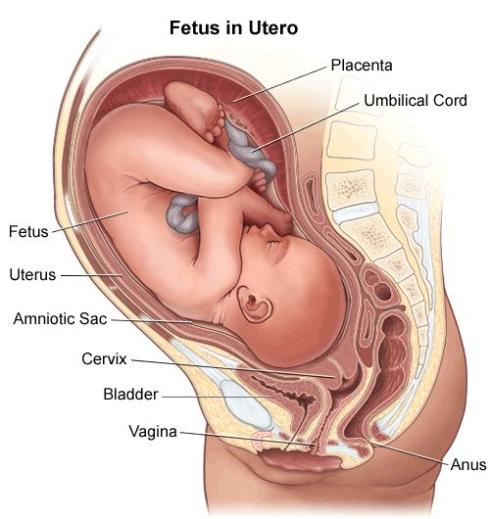

Once the embryo has reached the uterus 7 days after fertilisation, it can implant into the thickened, sticky and blood-rich endometrium. The implanted embryo grows into the uterine lining and starts to surround itself with a collection of membranes. Some of these membranes develop into structures in the placenta, but one the amnion has a different function altogether. The amnion produces a fluid called amniotic fluid that cushions the developing embryo and foetus right through pregnancy and to birth.

The main advantage of having the developing embryo in a sac of amniotic fluid is that it protects the embryo by cushioning against blows to the abdomen. It is also essential for allowing the foetus to move around inside the uterus thus allowing development of the muscular system. The amniotic fluid enters the babies lungs and can promote normal development there. The foetus will swallow amniotic fluid into its stomach and will produce urine into the amniotic fluid as well. Disgusting I know, but that’s babies for you……..

Amniotic fluid contains stem cells. In the future it may be possible to harvest these pluripotent cells and use them to create adult tissues for medical uses.

Role of the Placenta – Grade 9 Understanding for IGCSE Biology 3.11

There are two syllabus points in bold (only tested in paper 2) that refer to embryonic and foetal development. The first asks you to understand the role of the placenta in supplying the developing foetus with nutrients and oxygen and the second concerns the role of amniotic fluid in protecting the developing embryo.

Placenta

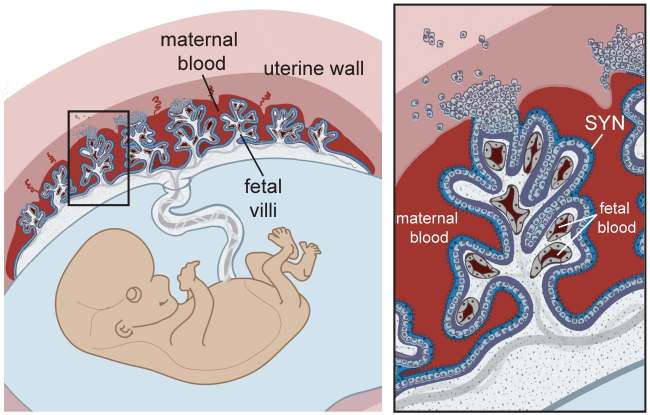

The placenta is in many ways a remarkable organ. It contains a mixture of maternal cells from the uterine lining and embryonic cells, but these cells from two genetically different individuals are capable of sticking together to form the placenta. The placenta is only present in the uterus once an embryo has successfully implanted a week or so after fertilisation has happened in the Fallopian Tubes. The placenta is linked to the foetus via the umbilical cord, a structure that contains an umbilical artery and vein carrying foetal blood to and from the placenta.

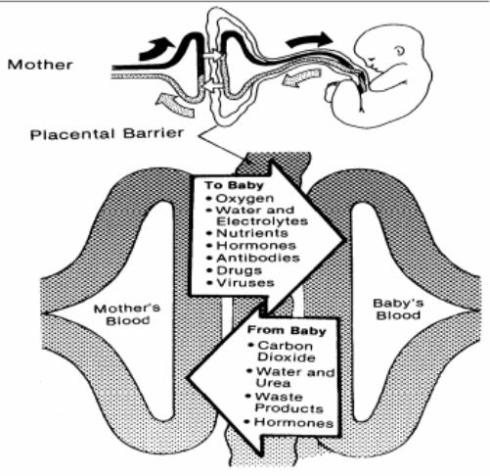

There is a key idea here that is very important. There is no mixing of maternal and foetal blood in the placenta. This would be disastrous for both mother and baby for a whole variety of reasons. The maternal blood is at a much higher pressure than the foetal blood and if the foetus were connected to the maternal circulatory system directly, its blood vessels would burst. The foetus and mother can have different blood groups of course and you may now that some blood groups are incompatible and can trigger clotting. So it is essential that there is never any mixing of blood. But what happens in the placenta is that mother’s blood empties into spaces in the placenta and babies’ blood is carried by the umbilical artery into capillaries that are found in finger-like projections called villi. This means there is a large surface area and a thin barrier between the two bloods and so exchange of materials by diffusion is possible.

The main function of the placenta then is to allow the exchange of materials between the foetal and maternal circulations. The developing foetus inside its mother’s uterus has no direct access to oxygen nor food molecules of course yet both are needed to allow healthy development. The foetus also needs a mechanism to get rid of the waste molecule, carbon dioxide that is being produced in all its cells all the time. Until the kidneys mature fully the foetus also has to get rid of urea, another excretory molecule that could build up to toxic concentrations unless removed from the growing foetus.

A few interesting points:

You will see that antibodies are small enough to cross the placenta. This gives the baby a passive immunity that can protect it for a short time from any pathogens it encounters.

Drugs such as alcohol and nicotine can cross the placenta. This is why it is so vital that pregnant mothers do not smoke and drink to ensure that the foetus’ development is not affected by these drugs.

Germination – Grade 9 Understanding for Biology GCSE 3.5 3.6

In the topic of sexual reproduction in plants, the final stage is often overlooked. I think it is helpful for students to think of this topic in several distinct stages.

- Flower Structure (hermaphrodite nature of most plants)

- Pollination (self v cross pollination; wind v insect pollinated flowers)

- Fertilisation (how does the pollen tube reach the egg cell to fertilise it?)

- Seed and Fruit formation (what forms what after fertilisation)

- Seed Dispersal (by animals, by wind, by water, by explosive means)

- Germination

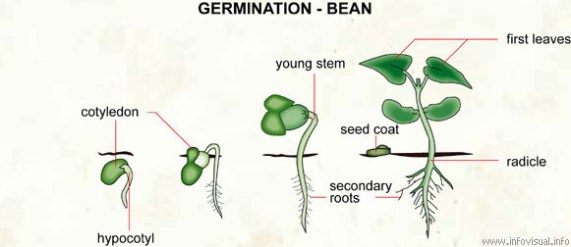

Once the seed has been dispersed there then follows a period of dormancy when nothing happens. In latitudes such as the UK this often is there to delay germination until the following spring when growing conditions become more favourable. The process of taking an inert seed and growing a new plant from it is called germination.

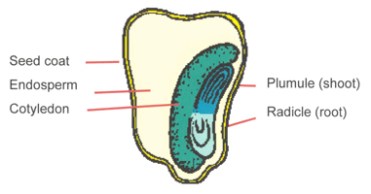

You don’t need to worry too much about the details of germination but there are a few vital parts of the process that GCSE candidates need to appreciate for A* marks. Firstly you should know the structure of a typical seed.

The seed coat or testa surrounds the seed and provides a tough waterproof container. Inside there are the embryonic plant (composed of a plumule and radicle), one or two seed leaves called cotyledons and a storage tissue called endosperm.

Germination starts when the seed starts to take up water by osmosis. There is an opening in the testa called the micropyle that allows water to move into the seed causing it to swell and thus rupture the seed coat to allow the embryo plant to emerge.

Water entering the seed also activates the embryo plant such that it starts to release digestive enzymes such as amylase. Amylase catalyses the digestion of starch into a simple sugar maltose. The endosperm and cotyledons contain energy stores in the form of starch, lipids and proteins and as these get broken down by the various enzymes, they provide the energy for the early growth of the seedling. The radicle emerges first and grows downwards (positive geotropism) and then the plumule or shoot grows upwards towards light (positive phototropism). Remember that throughout the early stages of this growth the energy required comes from stored food molecules in the seed. If you measure the mass of the plant during this phase, it would be decreasing. Only when the first leaves emerge above ground and the plant can start the process of photosynthesis will the overall mass start to increase.

How to score full marks on IGCSE Genetics questions? 3.23 3.25

This will be my final blog entry from Dubai. I will be flying home tomorrow with spirits refreshed by this amazing country and the positive and dynamic people I have met.

There will be a Mendelian genetics question in one of the two EdExcel IGCSE Biology papers. Examiners are people who like to stick to tried and tested formulae with setting questions and it’s always worked in the past, so why change now…?

You should welcome the genetics question when it appears for two reasons:

- If you understand what is going on and

- if you are prepared to set the answer out correctly (see below)

you can almost guarantee that you will score all the marks! And that’s what we want as full marks = top grade

The understanding you need for these questions is actually quite detailed and beyond what I can explain in this post. Check your understanding by answering the following questions:

- What is the difference in meaning between a gene and an allele?

- Why does the genotype of a person, plant, fruit fly or rabbit contain two alleles for each gene?

- What is different about the genotype of a gamete compared with every other cell in the body? Why are gametes different?

- How would you explain what is meant by a recessive allele?

- If two alleles are codominant, what does this mean? Give me a specific example in which this pattern of inheritance is found.

Good, I am assuming you have answered these questions fully using important terms like diploid, homologous chromosomes, phenotype, heterozygous correctly……

In which case, all that remains is to remind you how to set out a genetic diagram. I am not usually a proponent of slavishly following protocols but in producing a genetic diagram in an exam, you certainly should. There are usually five marks available for a question like this and only one of the marks is for getting the right answer. 20% = E grade and that is not what we want.

- Start with the phenotype of the parents – write mother and father’s phenotype down in full

- Then underneath the phenotype, write the genotype of the parents. (The letters to use for the two alleles will be given in the question and always use the letters suggested, don’t make up your own. Slavish following of protocol remember)

- The next bit is the first tricky bit. Write the alleles present in the gametes. Remember gametes are formed by meiosis and so only contain one member of each homologous pair of chromosomes – they will only have one allele from each pair in each cell. Draw circles around each gamete to show the examiner you understand they are individual cells.

- Draw a fertilisation table (called a Punnett square after Reginald Punnett – who says you don’t learn anything useful at GCSE?)

- Write out the offspring genotypes from the table

- Write out the offspring phenotypes underneath your list of offspring genotypes showing how they match up.

Answer the question. If asked for a probability, express it as a fraction or percentage. Those of you who follow the horses are sometimes tempted to write the probability as odds, but “3-1 the dwarf rabbit, 3-1 on the field” is not a good answer in your Biology exam…

If you do this you will always get all the marks.

Please remember:

The ratio of 3:1 is only found in the offspring of two heterozygous parents. Sometimes students seem to think that all genetic crosses produce offspring in this ratio. This doesn’t make any sense if you think about it for a moment but in an exam, thinking for a moment is not always easy.

If you look at phenotypes in a population, the dominant phenotype is not always more common that the recessive phenotype. This is something people find really difficult to get their head around. Think of the disease polydactyly in which suffers have an extra digit (e.g. Anne Boleyn) Polydactyly js caused by a dominant allele but I bet in your class at school, people with 5 digits on each hand are more common than those with 6. (A joke about schools in the Fens north of Cambridge has been removed in the interests of good taste)

As fertilisation is random, offspring will never exactly fit the expected Mendelian ratio. If you are given a cross in which peas produce offspring and 495 are smooth and 505 are wrinkled, you do not have to work out some complicated theory to explain this ratio. It will be a 1:1 ratio with the small differences due to random fertilisation

Good luck and keep working hard! Comments welcome as always – it does show me that someone is reading this stuff…….

Evolution for IGCSE Biology: Grade 9 Understanding 3.38 3.39

There are a few topics which you can pretty much guarantee will be tested somewhere in the two iGCSE Biology papers. There will be a genetics problem to solve (see later post) and in almost every year there is a question about the process of natural selection. These questions tend to be based around either the evolution of antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria or an animal example based around some adaptation.

Questions on evolution are usually worth four or five marks and I would suggest you always answer them with bullet points. Mark schemes for these questions are often similar and once you have revised the topic, some time spent with past questions and mark schemes would be time well spent.

Imagine you are set a question about cheetah and high speed running. (Everyone knows cheetah can run for short distances at up to 70 mph: so can the gazelle of course – that’s a coincidence isn’t it?) How did modern-day cheetah evolve to run so fast?

Key ideas to include in your answer:

1) Variation in cheetah population: in any population of cheetah at any point in their evolutionary history, some cheetah will just happen to be able to run a little faster than others. This continuous variation could be due to environmental factors (diet, access to gyms etc.) or it could be due to the combinations of genes they happen to have inherited from their parents, or more likely to a bit of both. Environmental causes of variation are not inherited of course but the genetic ones can be and that’s the key to natural selection.

2) Competition: variation by itself cannot lead to natural selection. If all cheetah survived to breed however slowly they ran, then high-speed cheetah would never have evolved. In my example, cheetah are competing with other cheetah for access to prey species. Gazelle run pretty quick too (I wonder why?) so cheetah who are slower than average will get less food. Conversely if you are a cheetah who just happens due to random genetic variation to be a little quicker than your neighbours, you will get more food, be more healthy and more likely to survive to adulthood.

3) If your particular combination of genes makes you more likely to survive, then you are more likely to breed and pass these genes onto future generations of cheetah. This process is called Natural Selection and it results in certain alleles becoming more frequent in a population over time. In this example, the alleles that produce aerodynamic, long-limbed and muscle-bound cheetah become more frequent over time while alleles building lethargic, over-weight and peaceful cheetah tend not to be passed on as well to future generations.

4) This produces a gradual change in the population over time. Selection is a cumulative process: small changes from one generation to the next can add up to big changes over thousands of generations.

NB This answer does not contain the word mutation and this is quite deliberate on my part. You want to make absolutely clear in your answer that at no point in the history of cheetah, did two slow-running cheetah parents give birth to a “mutant” cheetah with Usain Bolt like qualities. Mutation is a random change in the DNA of an organism and much of the genetic variation described above comes not from new mutations appearing but from the shuffling up of alleles into new combinations in meiosis. These new combinations of alleles can produce new phenotypes and these are the features on which selection can act.

But…… If you are writing about the evolution of antibiotic resistance in bacteria, this can be due to a single mutation. One altered gene can produce an enzyme that will breakdown antibiotic molecules or pump them out of a bacterial cell, so in this example it would be correct to talk about a random mutation occurring in the bacterial population. The key thing here is that these mutations have been occurring randomly for billions of years in bacteria. The mutation is totally independent of the use of antibiotics. All that has happened differently in the past 50 years is that for most of evolutionary history these random mutations would have been harmful to the survival chances of the bacterium unfortunate enough to acquire them. Now in an environment particularly in hospitals flush with antibiotics, these once harmful mutations can give the bacteria a massive selective advantage. Hence the evolution of strains of bacteria in hospitals resistant to a variety of different antibiotics e.g. MRSA and C. difficile

This is an essential topic to get your head around for the exam. Please comment on the blog post if you have any questions or contact me via Twitter.

Good luck!