Tagged: revision

Immunity: Grade 9 Understanding for Biology IGCSE 2.63B

The most complicated topic in the human transport topic is certainly immunisation. In a previous post, I said you should be able to answer the following two questions:

Why is it that the first time your body encounters measles virus, you suffer from the disease measles? Why will someone who has had measles as a baby (or been immunised against it) never contract the disease measles even though the virus might get into their body many subsequent times?

I thought in this post I should attempt to expand a little so as to provide answers to these two important questions. This understanding is quite complex for IGCSE but you cannot really see how immunity works unless you can work through each stage in the process.

Let’s pretend you are a new born baby and you get measles virus particles into your bloodstream from contact with an infected person. Remember viruses are not living organisms as they are not made of cells and have no metabolism. All they are is a tiny particle made of DNA (genetic material) surrounded by a protein coat.

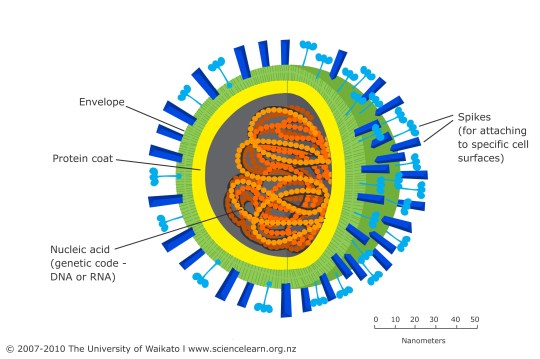

Look up a picture showing the structure of a virus particle in Google. This one comes from science learn.org.nz

The “spikes” on the surface of the virus particle are proteins that are essential to allow the virus to get inside a host cell. But they can also act as antigens allowing the immune system to recognise the virus as a foreign object and so mount an immune response to it.

In the body there are hundreds of billions of white blood cells called B lymphocytes. Each B lymphocyte is able to divide by mitosis over and over again to form a clone of cells called plasma cells. These plasma cells secrete a type of protein called an antibody which has a shape specific to the shape of the antigen such that it can bind to the antigen and neutralise it. (Can you think of another example in the specification where the shape of a protein is essential to its function?)

Now here is the first key piece of information needed in understanding immunity. Each B lymphocyte is only able to produce an antibody molecule with one particular shape. So the reason you need hundreds of billions of lymphocytes is to be able to produce antibodies that have the correct shape to combat hundreds of billions of possible shaped antigens on a lifetime of pathogen exposure.

Go back to your newborn baby exposed to measles virus. There might be only a handful of B lymphocytes in the babies’ body that just happen to be able to produce a shape of antibody specific to antigens on the surface of the measles virus. Before any antibodies can be produced, the “correct” B lymphocyte has to come into contact with measles virus particles and be activated. It then has to divide many times by mitosis to form a clone of plasma cells and the plasma cells have to differentiate and start producing antibodies. This whole process is called the primary response (first exposure hence primary) and it may take up to 8 days before any antibodies start appearing in the babies’ blood. What are the measles virus particles doing all this while? Well they are infecting host cells, damaging them and causing disease. This is why the baby will suffer from the disease measles.

The second key piece of information for immunity is this: when the B lymphocyte that has been activated divides by mitosis to form a clone, not all the cells produced form antibody-producing plasma cells. About 25% of the clone just remain as lymphocytes and are called memory cells. This is because they are long-lived cells that account for immunological memory.

Let’s pretend the baby gets better from measles due to the antibodies produced in the primary response. What happens if years later, the child goes to school and meets measles virus again for a second time? You all know that the child won’t get the disease measles this time. This is because the immune response is different second time round – the secondary response. The secondary response to antigen is quicker (no 8 day delay), larger (more antibodies made) and lasts for longer. This is because in a secondary response there are not just a handful of B lymphocytes in the body capable of making antibodies to combat measles virus. There are now millions of memory cells left over from the primary response that can all immediately “leap into life” and start making antibodies. These antibodies will be produced so quickly and in such large numbers that the virus particles will be eliminated before they have time to cause harm and disease. No harm caused to host cells therefore no disease measles this time round!

Finally, you know that you can have immunity to measles without having had the disease. This is because everyone in the UK sitting GCSE exams this summer will have been immunised against measles virus as a baby. You were injected with antigens from the surface of measles virus particles when you were a baby. These antigens by themselves could not give you measles (why not?) but they did cause a primary response to occur and memory cells to measles antigens be formed. So now if you do encounter measles virus, your body will mount a secondary response and you won’t get the disease. #result

Common misconception:

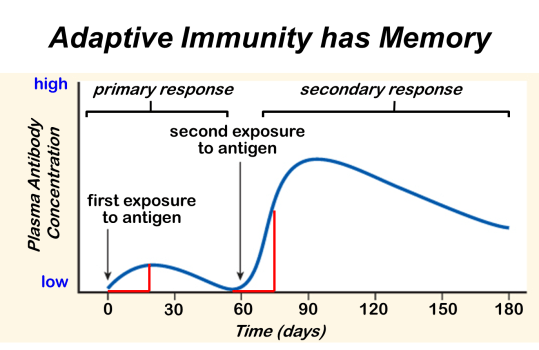

When answering questions on this topic in exams, candidates often think that it is the antibodies produced in the primary response that are left over to stop you getting measles later in life. Look at a graph showing primary and secondary responses to antigen such as the one below.

This graph shows how antibody concentration in the blood changes in the primary and secondary immune response.

Antibodies are proteins and you can see they have a half-life in the blood of a few weeks. (The liver breaks down proteins in the blood as one of its many functions) So all the antibodies from a primary response will have been removed within a few months of the first exposure. Immunity can last a lifetime and this is because memory cells can survive as long as you do. Unlike antibodies they can hang around in your blood and lymph nodes for the rest of your life. If you live to be a hundred, you still won’t catch measles more than once.

This is a tricky topic so do please comment on this post if you have any questions. Work hard at revision – it will be worth it in the end….. (At least with Biology revision, it is fascinating stuff isn’t it?)

Human Transport IGCSE – a few pointers for Grade 9 Understanding 2.59, 2.63B, 2.69

I have had a request from a student to write about the level of details needed in the section of the specification on human transport. Here are the relevant bullet points from the specification, together with a very brief outline of the kinds of details to learn:

- Blood composition 55% plasma, 45% cells (red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets)

- Plasma functions – transport of dissolved carbon dioxide, dissolved glucose, urea, salts etc.and transport of heat around body

- Red Blood cells – no nucleus, each cell packed full of 250,000 molecules of haemoglobin, biconcave disc shape to squeeze through narrow capillaries

- Phagocytes/Lymphocytes – two types of white blood cell, phagocytes engulf foreign organisms in blood by phagocytosis, lymphocytes do many functions in defending the body against disease but many produce antibodies

- Vaccination with reference to memory cells and primary v secondary response (see below)

- Functions of clotting and role of platelets (prevent infection, stop blood loss – platelets play central role in clotting as they produce chemicals that are needed for clotting cascade

- Structure and function of the heart (learn names of chambers, blood vessels, names of four sets of valves and what they do)

- Role of adrenaline in changing heart rate during exercise (speeds it up to maximise cardiac output to muscles)

- Structure and functions of arteries/veins/capillaries (simple bookwork)

- General plan of circulation including heart, lungs, liver and kidneys (see below)

The two sections that are perhaps hardest to interpret are the ones on vaccination and the general plan of the circulation.

1) Key terms in vaccination to understand:

- Antigen

- Antibody

- Lymphocyte

- Clonal Selection theory

- Memory cells

- Effector cells (plasma cells)

- Primary response

- Secondary response

At the end of the process, you should be able to provide a clear concise answer to the following question?

Why is it that the first time your body encounters measles virus, you suffer from the disease measles? Why will someone who has had measles as a baby (or been immunised against it) never contract the disease measles even though the virus might get into their body many subsequent times?

2) The blood vessels involved in the four organs mentioned are described below.

Heart – receives blood from the coronary arteries which branch off the aorta before it has even left the heart: Why doesn’t the cardiac muscle in the heart just get the oxygen and nutrients it needs from the blood in the chambers?

Lungs – pulmonary artery takes blood from right ventricle to the lungs, pulmonary vein return oxygenated blood to the heart and empty it into the left atrium. What is unique about the composition of the blood in the pulmonary artery?

Liver – has a most unusual blood supply. There is a hepatic artery that branches off the aorta and brings oxygenated blood to the liver. Blood also goes to the liver in the hepatic portal vein which brings blood from the small intestine. Blood in the hepatic portal vein will contain lots of dissolved glucose and amino acids, both of which are processed in the liver. Deoxygenated blood leaves the liver in the hepatic vein. Find a diagram to show the arrangement of these three blood vessels.

Kidney – straightforward blood supply in that there is a renal artery and a renal vein. (important idea is that the renal artery is much much bigger than you would expect from the size of the organs: 25% of the cardiac output of blood flows through the kidneys on each circuit) Why do you think this is?

I hope this helps – more to follow when I get home from my holidays tomorrow afternoon…..

Do Something Today……

Advice for PMG’s D block Biologists

How to score full marks on IGCSE Genetics questions? 3.23 3.25

This will be my final blog entry from Dubai. I will be flying home tomorrow with spirits refreshed by this amazing country and the positive and dynamic people I have met.

There will be a Mendelian genetics question in one of the two EdExcel IGCSE Biology papers. Examiners are people who like to stick to tried and tested formulae with setting questions and it’s always worked in the past, so why change now…?

You should welcome the genetics question when it appears for two reasons:

- If you understand what is going on and

- if you are prepared to set the answer out correctly (see below)

you can almost guarantee that you will score all the marks! And that’s what we want as full marks = top grade

The understanding you need for these questions is actually quite detailed and beyond what I can explain in this post. Check your understanding by answering the following questions:

- What is the difference in meaning between a gene and an allele?

- Why does the genotype of a person, plant, fruit fly or rabbit contain two alleles for each gene?

- What is different about the genotype of a gamete compared with every other cell in the body? Why are gametes different?

- How would you explain what is meant by a recessive allele?

- If two alleles are codominant, what does this mean? Give me a specific example in which this pattern of inheritance is found.

Good, I am assuming you have answered these questions fully using important terms like diploid, homologous chromosomes, phenotype, heterozygous correctly……

In which case, all that remains is to remind you how to set out a genetic diagram. I am not usually a proponent of slavishly following protocols but in producing a genetic diagram in an exam, you certainly should. There are usually five marks available for a question like this and only one of the marks is for getting the right answer. 20% = E grade and that is not what we want.

- Start with the phenotype of the parents – write mother and father’s phenotype down in full

- Then underneath the phenotype, write the genotype of the parents. (The letters to use for the two alleles will be given in the question and always use the letters suggested, don’t make up your own. Slavish following of protocol remember)

- The next bit is the first tricky bit. Write the alleles present in the gametes. Remember gametes are formed by meiosis and so only contain one member of each homologous pair of chromosomes – they will only have one allele from each pair in each cell. Draw circles around each gamete to show the examiner you understand they are individual cells.

- Draw a fertilisation table (called a Punnett square after Reginald Punnett – who says you don’t learn anything useful at GCSE?)

- Write out the offspring genotypes from the table

- Write out the offspring phenotypes underneath your list of offspring genotypes showing how they match up.

Answer the question. If asked for a probability, express it as a fraction or percentage. Those of you who follow the horses are sometimes tempted to write the probability as odds, but “3-1 the dwarf rabbit, 3-1 on the field” is not a good answer in your Biology exam…

If you do this you will always get all the marks.

Please remember:

The ratio of 3:1 is only found in the offspring of two heterozygous parents. Sometimes students seem to think that all genetic crosses produce offspring in this ratio. This doesn’t make any sense if you think about it for a moment but in an exam, thinking for a moment is not always easy.

If you look at phenotypes in a population, the dominant phenotype is not always more common that the recessive phenotype. This is something people find really difficult to get their head around. Think of the disease polydactyly in which suffers have an extra digit (e.g. Anne Boleyn) Polydactyly js caused by a dominant allele but I bet in your class at school, people with 5 digits on each hand are more common than those with 6. (A joke about schools in the Fens north of Cambridge has been removed in the interests of good taste)

As fertilisation is random, offspring will never exactly fit the expected Mendelian ratio. If you are given a cross in which peas produce offspring and 495 are smooth and 505 are wrinkled, you do not have to work out some complicated theory to explain this ratio. It will be a 1:1 ratio with the small differences due to random fertilisation

Good luck and keep working hard! Comments welcome as always – it does show me that someone is reading this stuff…….

Evolution for IGCSE Biology: Grade 9 Understanding 3.38 3.39

There are a few topics which you can pretty much guarantee will be tested somewhere in the two iGCSE Biology papers. There will be a genetics problem to solve (see later post) and in almost every year there is a question about the process of natural selection. These questions tend to be based around either the evolution of antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria or an animal example based around some adaptation.

Questions on evolution are usually worth four or five marks and I would suggest you always answer them with bullet points. Mark schemes for these questions are often similar and once you have revised the topic, some time spent with past questions and mark schemes would be time well spent.

Imagine you are set a question about cheetah and high speed running. (Everyone knows cheetah can run for short distances at up to 70 mph: so can the gazelle of course – that’s a coincidence isn’t it?) How did modern-day cheetah evolve to run so fast?

Key ideas to include in your answer:

1) Variation in cheetah population: in any population of cheetah at any point in their evolutionary history, some cheetah will just happen to be able to run a little faster than others. This continuous variation could be due to environmental factors (diet, access to gyms etc.) or it could be due to the combinations of genes they happen to have inherited from their parents, or more likely to a bit of both. Environmental causes of variation are not inherited of course but the genetic ones can be and that’s the key to natural selection.

2) Competition: variation by itself cannot lead to natural selection. If all cheetah survived to breed however slowly they ran, then high-speed cheetah would never have evolved. In my example, cheetah are competing with other cheetah for access to prey species. Gazelle run pretty quick too (I wonder why?) so cheetah who are slower than average will get less food. Conversely if you are a cheetah who just happens due to random genetic variation to be a little quicker than your neighbours, you will get more food, be more healthy and more likely to survive to adulthood.

3) If your particular combination of genes makes you more likely to survive, then you are more likely to breed and pass these genes onto future generations of cheetah. This process is called Natural Selection and it results in certain alleles becoming more frequent in a population over time. In this example, the alleles that produce aerodynamic, long-limbed and muscle-bound cheetah become more frequent over time while alleles building lethargic, over-weight and peaceful cheetah tend not to be passed on as well to future generations.

4) This produces a gradual change in the population over time. Selection is a cumulative process: small changes from one generation to the next can add up to big changes over thousands of generations.

NB This answer does not contain the word mutation and this is quite deliberate on my part. You want to make absolutely clear in your answer that at no point in the history of cheetah, did two slow-running cheetah parents give birth to a “mutant” cheetah with Usain Bolt like qualities. Mutation is a random change in the DNA of an organism and much of the genetic variation described above comes not from new mutations appearing but from the shuffling up of alleles into new combinations in meiosis. These new combinations of alleles can produce new phenotypes and these are the features on which selection can act.

But…… If you are writing about the evolution of antibiotic resistance in bacteria, this can be due to a single mutation. One altered gene can produce an enzyme that will breakdown antibiotic molecules or pump them out of a bacterial cell, so in this example it would be correct to talk about a random mutation occurring in the bacterial population. The key thing here is that these mutations have been occurring randomly for billions of years in bacteria. The mutation is totally independent of the use of antibiotics. All that has happened differently in the past 50 years is that for most of evolutionary history these random mutations would have been harmful to the survival chances of the bacterium unfortunate enough to acquire them. Now in an environment particularly in hospitals flush with antibiotics, these once harmful mutations can give the bacteria a massive selective advantage. Hence the evolution of strains of bacteria in hospitals resistant to a variety of different antibiotics e.g. MRSA and C. difficile

This is an essential topic to get your head around for the exam. Please comment on the blog post if you have any questions or contact me via Twitter.

Good luck!

Eutrophication – the least glamorous topic in IGCSE Biology 4.16 4.17

This is a topic it is easy to overlook in your revision: water pollution by sewage is hardly glamorous and when you combine it with the limited excitement of learning about fertilisers, you don’t have to be a genius to see why many students leave it out. But examiners seem to like eutrophication so it is worth making sure you are going to score full marks on any question they set.

Starting point in your understanding for this topic should be that what limits plant growth in many circumstances, and often in aquatic ecosystems, is the availability to the plant of nitrate ions. A nitrate ion (NO3-) is essential for the plant to make amino acids, and hence proteins and also DNA. Cells need more DNA and proteins to divide and grow so farmers spray extra nitrate ions onto their fields in fertilisers.

Nitrate ions are very soluble in water so if it rains, they can easily dissolve as the rain water passes through the soil a process known as “leaching”. These nitrate ions can thus end up in freshwater, for example streams and ponds where they have exactly the same effect as in the soil – they cause excessive plant growth. The plants in freshwater are often types of algae and if you have far too much nitrate in the water, this can cause an algal bloom. This excessive growth of plants is called eutrophication (or more properly hypertrophication)

Now the eutrophication story then proceeds like this….

If there is an algal bloom, this can eventually cover the surface of a pond so that light doesn’t penetrate to the multicellular plants that live on the bottom, the beautifully named “bottom-dwellers”. No light for these plants means they can’t photosynthesise and so they die. In the water there will be aerobic bacteria that act as decomposers and so if there is loads of dead material in the water, the populations of these bacterial decomposers will rapidly rise to break down the detritus. These bacteria remove dissolved oxygen efficiently from the water as their numbers go up (remember they are aerobic bacteria), so water quality rapidly falls. The lowering oxygen concentration in the water will itself cause animals from small invertebrates to larger fish to die and so a vicious circle is set up: less oxygen = more dead organisms = more decomposers = less oxygen.

The consequences for a pond in these conditions are very damaging. The complex ecosystem involving producers, consumers, food chains and so on is replaced by one with algae, decomposing bacteria and a few organisms that can survive in anaerobic conditions.

Anything that increases the numbers of decomposers in a freshwater ecosystem can cause eutrophication and the consequences described. The commonest cause is agricultural run off from fertilisers (nitrates/phosphates etc.) but untreated sewage can cause similar consequences. The decomposers need to break down the sewage, releasing nitrate ions into the water that cause eutrophication. The murkiness of the water can also kill bottom-dwellers directly and set the whole cycle off.

Eutrophication is a sequential process and often examiners use this question to test your ability to organise your answer properly. I would always answer a four or five marker on this topic with bullet points rather than a paragraph of text. Why do you think this is?

Now make a summary diagram to show eutrophication and answer a few IGCSE questions from the booklet.

Work hard!

Revision tips – a few topics that should be compulsory

Students often choose to revise topics that either they know they find interesting or perhaps ones that they already understand. Working on the idea that you will have 10 hours at most to revise the whole IGCSE specification this holiday, this should be avoided if at all possible. Use the “traffic lights” checklists in the revision booklets to target your revision within a particular topic.

Topics that boys often avoid revising (are some of these just a little dull?) but which examiners seem to like to test are given below:

- Deforestation and link with climate change

- Cycles in Ecology (Carbon, Nitrogen and Water)

- Natural Selection (you can almost guarantee there will be a question on this)

- Genetic Engineering (pay close attention to the syllabus points about specific examples and ethical objections)

- Variety of Living Organisms (Classification) – there are loads of specific details about the Five Kingdoms with specific examples: go through this section of the specification really carefully!

- Food – balanced diet idea and the specific vitamins mentioned in the specification

- Air pollution – sulphur dioxide (acid rain) and carbon monoxide

- Fermenters – how to grow bacteria and the specific conditions needed

- Fish Farming – remember someone in the exam board loves fish farming! Make sure you understand the specific details of how the fish farm is set up and the potential problems: this tiny part of the syllabus has been over-represented massively in the past few years: please take care to ensure you don’t get caught out by another fish farming question…..

The basic message in this post is this: your course is not IGCSE Human Biology so make sure you don’t just revise for this!

Keep working hard and tweet me with any questions or make a comment on this blog post.

PMG

Revision tips for IGCSE Biology students

The syllabus has now been completed for the PMG Y11 Biologists so for the next few weeks the focus shifts onto your personal work and learning. I am available throughout the Easter break of course so please email/tweet etc. with any questions or problem areas. I will try to post a few interesting things onto this blog to keep your motivation levels up!

The main challenge for you looking ahead to these exams is to master the breadth of knowledge and understanding needed. There are few areas that are conceptually too challenging but there is plenty of content to learn and this can only be achieved with organised revision.

Here are a few PMG tips for revision planning:

1) Time is Limited so you need to make the very best use of it in every revision session for Biology. Every session you work on Biology you need to be actively using various parts of your brain not just the visual cortex. Don’t read but instead make summary notes, flow diagrams, Flash Cards etc. Then practise questions, copy down mark schemes onto card etc. Make revision movies or Powerpoints – make revision fun!

2) Your textbook should now come into its own. This book has been specifically written for our specification so it should include all the subjects you need to know about with no extraneous material. I would use this textbook now as your primary source for revision, using notes and other sources when needed if a particular idea is unclear.

3) You now have three booklets of past paper questions (together with mark schemes if you have been to my lab to collect them!) These booklets should be used for testing your own understanding once you have revised a particular topic. Don’t ever look at the MS unless you have attempted the question: this tricks you into an alternative reality in which you think “oh yes I would have said that”. Don’t fall into the revision trap of thinking past papers by themselves are the answer.

4) Revision is not about how many hours: it is about how much you have learned, understood, remembered from the time you spend. If you do the calculations we talked about in school, I think during the holiday you will have at most 10 hours in total for Biology. Use this time wisely.

Finally a few general tips about organising your revision. My experience with many years of Y11 boys over too many years is that you will be much more productive if you get up in the mornings. Ask your Mum for help with this: tell her she can be really useful to you by ensuring you get up before 8am every day! Divide the day into three two and a quarter hour slots. Always work in the morning slot and then choose one of the two others each day.

Morning: 9.30am – 11.45am

Afternoon: 1.30pm – 3.45pm

Evening: 5pm – 7.15pm (timing can vary depending on when you eat supper)

And finally do the sensible things you all know but can sometimes get over-looked: sleep 8/9 hours every night but no more , eat a proper breakfast, drink plenty of water through the day and use fresh fruit as a treat… I know you all can do really well in the summer exams – there are no excuses on offer here. Work hard, enjoy the challenge and step up to it and you will be well rewarded in August.