Category: Section 2: Structures and Functions in Living Organisms

Skin – Grade 9 Understanding for IGCSE Biology 2.93

The skin as you all know is the largest organ in the human body. It has a variety of functions including providing a water-tight barrier to minimise evaporation from the cells; it is also a habitat for billions of bacteria that live on the skin, the so-called skin flora and it contains a variety of sensory receptors that provide information about the external world to our central nervous systems. The iGCSE specification requires you to know about the role of skin in thermoregulation.

The skin is made up of an outer layer of dead cells called the epidermis that contains sensory nerve endings. Beneath this is the dermis which is made of living cells and blood vessels, sweat glands, hair follicles and other specialised sensory receptors, e.g. for touch. Underneath the dermis there is a subcutaneous tissue that in humans is packed full of adipose cells that store lipids.

The skin is involved in thermoregulation both as a receptor and more significantly as an effector.

The skin’s role as a receptor in thermoregulation

The brain receives information about temperature from two sets of thermoreceptors. There are receptors in the hypothalamus that measure the temperature of the blood passing through the brain. This provides information about core body temperature. In the skin there are two types of thermoreceptors, called hot and cold receptors, that together monitor the external temperature. Information from both these sets of receptors is used by thermoregulatory centres in the hypothalamus to regulate your body temperature.

The skin’s role as an effector in thermoregulation

The skin is the principle effector organ for thermoregulation. This is because it is found at the boundary between your cells and the external environment and so heat gain and heat loss happen through it. The skin has three ways of altering the heat gain/loss depending on nerve impulses from the CNS.

1) Sweating

Humans have sweat glands spread over almost all the surface of the skin. These glands secrete a watery liquid, sweat that contains a solution of salts and a tiny amount of urea dissolved in large volumes of water. Sweat is only produced when the body temperature is too high as the evaporation of sweat from the surface of the skin leads to a cooler skin. How does this process work?

The main idea to understand is that the sweat itself is not in any way cool. Sweat is made in sweat glands from blood plasma so if the blood is getting too hot, the sweat will be hot as well. But it takes energy to evaporate water (to turn it from the liquid to the vapour state) and this energy (called the latent heat of vapourisation) is taken as heat energy from the skin. So as sweat evaporates, it uses thermal energy from the skin to turn the water molecules in sweat into a vapour. This evaporative cooling leaves the skin cooler once the sweat has evaporated than it was at the start.

2) Hairs

Hairs on the skin play an important role in thermoregulation in many mammals but not really in our species. If the body temperature drops, the CNS causes hair erector muscles to contract and pull the hair to a more vertical position in the follicle. If an animal’s hairs stand on end, a thicker layer of air is trapped between them and so the body is better insulated against heat loss. Humans are relatively hairless and the only thing that really happens in us when the hair erector muscles contract is that we get “goose bumps”.

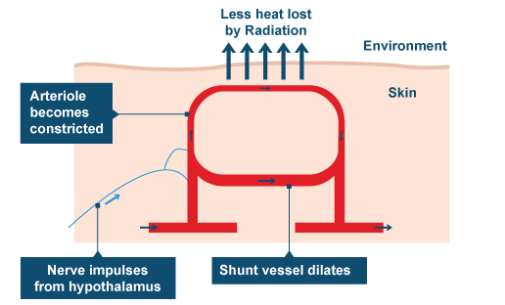

3) Shifting patterns of Blood flow in the skin

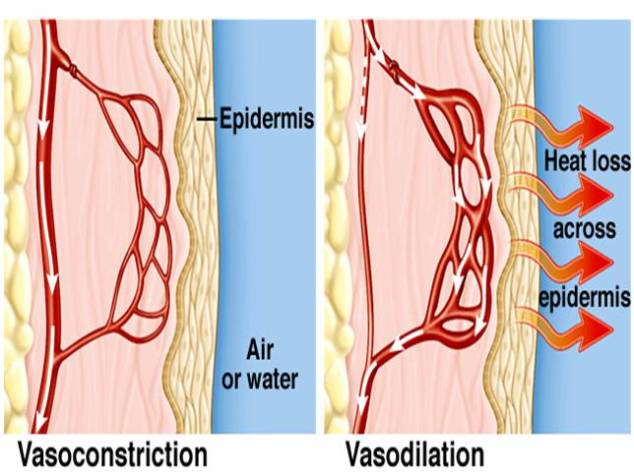

This is the main effector mechanism in human thermoregulation but it is also the one that tends to catch exam candidates out. Please make sure you understand this process fully and can explain this section of work very well indeed. If the body is getting too cold, the pattern of blood flow switches in the skin so less blood flows in the capillary beds near the surface of the skin and more blood is retained deeper in the skin structure. This is achieved by narrowing the arterioles that supply the capillary beds near the surface (arterioles and arteries have plenty of muscle in their walls that can contract to narrow the lumen of the blood vessel) This narrowing of arterioles is called vasoconstriction.

The converse happens when the body is getting too warm. The muscle in the walls of these arterioles now relaxes to widen the lumen, thus allowing more blood to flow in capillary beds near the surface. This vasodilation allows more heat to be lost from the blood by conduction, convection and radiation and so the blood leaving the skin has lost more heat to the external environment.

You will notice that at no point in these explanations of vasoconstriction and vasodilation do I mention capillaries in the skin moving deeper or nearer the surface. For some reason every year, GCSE candidates think that the reason you look redder when you are hot is because capillaries in the skin move nearer the surface. This cannot be true – blood vessels have a fixed position in the body for a start – but now you should understand that you look redder when you are hot because the capillaries that happen to be near the surface are having a greater volume of blood per minute flowing through them because of vasodilation. If you find yourself in the exam writing about capillaries moving in response to a change in temperature, please stop writing, take a deep breath, count to ten and then cross it all out and start again!

Xylem transport – Grade 9 Understanding for IGCSE Biology 2.54, 2.55B, 2.56B

The topic of plant transport can appear quite complicated but you will see from your past paper booklets that the questions examiners tend to set on it are much more straightforward.

The key piece of understanding is to realise that there are two transport systems in plants, learn their names and what they transport.

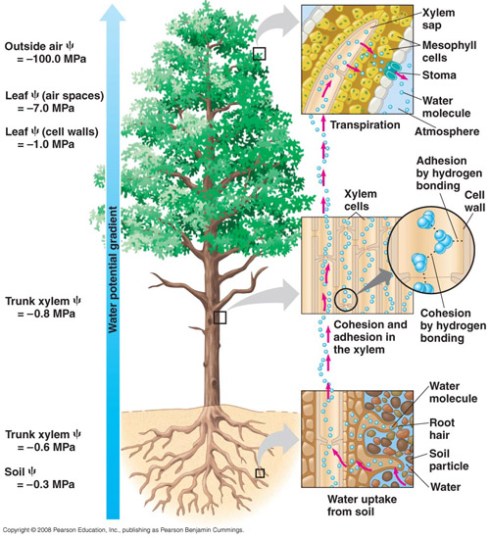

- Xylem vessels move water and mineral ions from the roots to the leaves.

- Phloem sieve tubes move sugars, notably sucrose, and amino acids around the plant. Both of these molecules are made in photosynthesis in the leaves and so can be transported from the leaves to the areas in the plant where they are needed.

Water is needed for photosynthesis of course in the leaves (remember that rain water cannot enter leaves directly because of the waxy cuticle on the surface of the leaf). All the water that is used in photosynthesis is absorbed in the roots from the soil and moved up the plant in the xylem vessels. Minerals such as nitrate, phosphate and magnesium ions are also required in the leaves for making amino acids, DNA and chlorophyll respectively. These minerals are moved up the plant along with the water in the xylem.

How does water enter the roots from the soil?

Water molecules can only enter root hair cells (and indeed can only cross any cell membrane) by one mechanism and that is OSMOSIS. If you understand the mechanism of osmosis that is great but don’t worry too much about it at this stage. You need to know that osmosis is a net movement of water from a dilute solution to a more concentrated solution across a partially permeable membrane.

How do mineral ions enter the roots from the soil?

Minerals are pumped into the root hair cells from the soil using ACTIVE TRANSPORT. This a process that uses energy from respiration in the cell to move ions against their concentration gradient (so from a lower concentration in the soil to a higher concentration inside the cell cytoplasm.)

What do we know about xylem vessels?

The cells that water and minerals are transported in are called xylem vessels. They have some interesting specialisations for this function. They are dead cells that are empty with no cytoplasm or nucleus. The end walls of these cells break down to provide a continuous unbroken column of water all the way up the plant. The cell walls of xylem vessels are thick and strengthened and waterproofed with a chemical called lignin.

What causes the water to move up the xylem?

Clearly it will take energy from somewhere to move water against gravity all the way up a plant from the roots to the leaves. The key question here is what provides the energy for this movement? There is no pumping of water up the plant and indeed the plant spends no energy at all on water movement. The answer is that it is the heat energy from the sun that evaporates water in the leaves that provides the energy for water movement. When you combine this with the fact that water molecules are “sticky” – they are attracted to their neighbours by a type of weak bond called a hydrogen bond – you can see that the water evaporating into the air spaces in the leaf can pull water molecules up the continuous column of water found in the xylem. The proper adjective for this stickiness is cohesive and you should know the name for the evaporation of water in the leaves (Transpiration)

A Simple Reflex Arc: Grade 9 Understanding for IGCSE Biology 2.90

GCSE Biology students often find the reflex arc a difficult topic in the section on human coordination and response. This is because it is the only type of response they learn about and doesn’t really fit into a sensible flow of ideas on the various types of behaviours organisms can show. But it is not too complicated, at least if you restrict yourself to ideas that might be tested in the iGCSE exam.

Prior Knowledge (you need to understand these things before you can appreciate a reflex arc)

- basic structure of a neurone/nerve cell

- three different kinds of neurones – sensory, motor and relay – and where they are found in the body

- nerve impulses are electrical events that travel at up to 100ms-1 along nerve cells but cross synapses much more slowly by diffusion of a chemical called a neurotransmitter

Reflex responses

Most human behaviours are complex and involve millions of neurones interacting in the brain. Our ability to link stimuli (changes in the environment) with an appropriate response can develop over time, can be modified by past experience and can produce different outcomes depending on the circumstances. For example if you see a fast moving spherical object moving towards your head, you might head it (football), catch it (cricket), hit it (cricket again), duck out of the way (cricket again) or eat it (flying Malteser)

A simple reflex response is much more straightforward: the same stimulus always produces the same response. It does not need to be learned but is innate (you are born with it) and in humans, reflex responses tend to be involved in protecting the body from harm or maintaining posture. The example we look at is called a withdrawal reflex to a painful stimulus e.g. touching a hot plate on a cooker.

The response to this is that you contract muscles in your arm to move your hand away from the hot plate. The key idea is that you will do this before you feel the heat or burn the skin. The sequence of events is

- touch the hot plate (pain receptors stimulated in the skin)

- move your arm away (reflex arc)

- feel the pain (brain receives the nerve impulses and a conscious sensation of pain is felt

The reason that you move your arm away before you feel anything is that your brain is not involved in this response. This produces a rapid, involuntary reaction called a reflex response. The reason the response is so rapid is that at most three neurones are involved in linking the painful stimulus to the response. The arrangement of these three neurones is called a reflex arc.

The cell that detects the stimulus is called a sensory neurone. One end of this cell is a pain receptor in the skin and the other end of this individual cell is found in the spinal cord (see diagram above) Neurones can be very long cells! The sensory neurone forms a synapse (junction) with a relay neurone found entirely in the grey matter in the centre of the spinal cord and this in turn synapses with a motor neurone. The cell body of the motor neurone is on the spinal cord and the other end of this individual cell is a synapse with a skeletal muscle in the arm.

The cell that detects the stimulus is called a sensory neurone. One end of this cell is a pain receptor in the skin and the other end of this individual cell is found in the spinal cord (see diagram above) Neurones can be very long cells! The sensory neurone forms a synapse (junction) with a relay neurone found entirely in the grey matter in the centre of the spinal cord and this in turn synapses with a motor neurone. The cell body of the motor neurone is on the spinal cord and the other end of this individual cell is a synapse with a skeletal muscle in the arm.

Synapses are the things that slow nerve impulses down and as this whole pathway only includes two synapses (sensory-relay and relay-motor) the response will be as fast as possible. The response is involuntary as the brain is not involved.

In humans, we can modify most reflex responses using the conscious parts of our brain. As the sensory neurone synapses with the relay neurone in the diagram, it will also synapse with other neurones carrying nerve impulses up to the brain. This is why touching a hot plate will hurt (the feeling of pain is in the brain). There will also be neurones from the brain that can modify the synapse between the relay and motor neurone. If I told you that I would pay anyone who can touch a hot plate for 2 seconds $10,000 (although of course I don’t have $10,000) many of you would be able to force yourself not to pull your arm away from the hotplate when you touch it. You could overcome the reflex response with signals from your brain which would know how much fun you could have with $10,000.

Immunity: Grade 9 Understanding for Biology IGCSE 2.63B

The most complicated topic in the human transport topic is certainly immunisation. In a previous post, I said you should be able to answer the following two questions:

Why is it that the first time your body encounters measles virus, you suffer from the disease measles? Why will someone who has had measles as a baby (or been immunised against it) never contract the disease measles even though the virus might get into their body many subsequent times?

I thought in this post I should attempt to expand a little so as to provide answers to these two important questions. This understanding is quite complex for IGCSE but you cannot really see how immunity works unless you can work through each stage in the process.

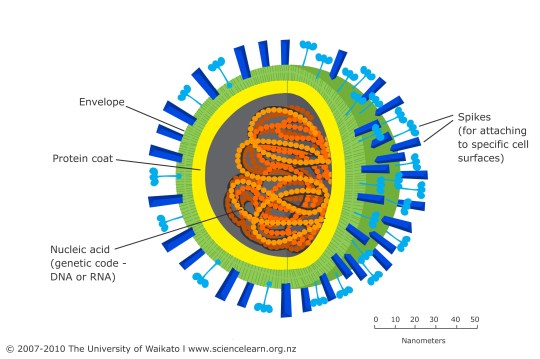

Let’s pretend you are a new born baby and you get measles virus particles into your bloodstream from contact with an infected person. Remember viruses are not living organisms as they are not made of cells and have no metabolism. All they are is a tiny particle made of DNA (genetic material) surrounded by a protein coat.

Look up a picture showing the structure of a virus particle in Google. This one comes from science learn.org.nz

The “spikes” on the surface of the virus particle are proteins that are essential to allow the virus to get inside a host cell. But they can also act as antigens allowing the immune system to recognise the virus as a foreign object and so mount an immune response to it.

In the body there are hundreds of billions of white blood cells called B lymphocytes. Each B lymphocyte is able to divide by mitosis over and over again to form a clone of cells called plasma cells. These plasma cells secrete a type of protein called an antibody which has a shape specific to the shape of the antigen such that it can bind to the antigen and neutralise it. (Can you think of another example in the specification where the shape of a protein is essential to its function?)

Now here is the first key piece of information needed in understanding immunity. Each B lymphocyte is only able to produce an antibody molecule with one particular shape. So the reason you need hundreds of billions of lymphocytes is to be able to produce antibodies that have the correct shape to combat hundreds of billions of possible shaped antigens on a lifetime of pathogen exposure.

Go back to your newborn baby exposed to measles virus. There might be only a handful of B lymphocytes in the babies’ body that just happen to be able to produce a shape of antibody specific to antigens on the surface of the measles virus. Before any antibodies can be produced, the “correct” B lymphocyte has to come into contact with measles virus particles and be activated. It then has to divide many times by mitosis to form a clone of plasma cells and the plasma cells have to differentiate and start producing antibodies. This whole process is called the primary response (first exposure hence primary) and it may take up to 8 days before any antibodies start appearing in the babies’ blood. What are the measles virus particles doing all this while? Well they are infecting host cells, damaging them and causing disease. This is why the baby will suffer from the disease measles.

The second key piece of information for immunity is this: when the B lymphocyte that has been activated divides by mitosis to form a clone, not all the cells produced form antibody-producing plasma cells. About 25% of the clone just remain as lymphocytes and are called memory cells. This is because they are long-lived cells that account for immunological memory.

Let’s pretend the baby gets better from measles due to the antibodies produced in the primary response. What happens if years later, the child goes to school and meets measles virus again for a second time? You all know that the child won’t get the disease measles this time. This is because the immune response is different second time round – the secondary response. The secondary response to antigen is quicker (no 8 day delay), larger (more antibodies made) and lasts for longer. This is because in a secondary response there are not just a handful of B lymphocytes in the body capable of making antibodies to combat measles virus. There are now millions of memory cells left over from the primary response that can all immediately “leap into life” and start making antibodies. These antibodies will be produced so quickly and in such large numbers that the virus particles will be eliminated before they have time to cause harm and disease. No harm caused to host cells therefore no disease measles this time round!

Finally, you know that you can have immunity to measles without having had the disease. This is because everyone in the UK sitting GCSE exams this summer will have been immunised against measles virus as a baby. You were injected with antigens from the surface of measles virus particles when you were a baby. These antigens by themselves could not give you measles (why not?) but they did cause a primary response to occur and memory cells to measles antigens be formed. So now if you do encounter measles virus, your body will mount a secondary response and you won’t get the disease. #result

Common misconception:

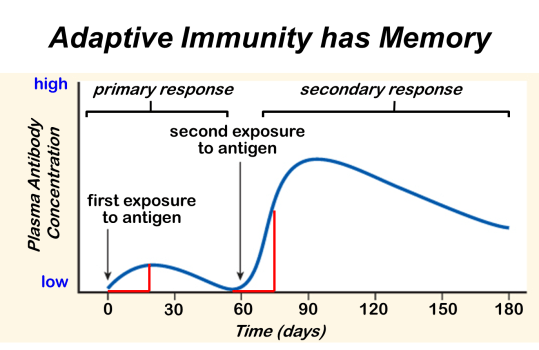

When answering questions on this topic in exams, candidates often think that it is the antibodies produced in the primary response that are left over to stop you getting measles later in life. Look at a graph showing primary and secondary responses to antigen such as the one below.

This graph shows how antibody concentration in the blood changes in the primary and secondary immune response.

Antibodies are proteins and you can see they have a half-life in the blood of a few weeks. (The liver breaks down proteins in the blood as one of its many functions) So all the antibodies from a primary response will have been removed within a few months of the first exposure. Immunity can last a lifetime and this is because memory cells can survive as long as you do. Unlike antibodies they can hang around in your blood and lymph nodes for the rest of your life. If you live to be a hundred, you still won’t catch measles more than once.

This is a tricky topic so do please comment on this post if you have any questions. Work hard at revision – it will be worth it in the end….. (At least with Biology revision, it is fascinating stuff isn’t it?)

Human Transport IGCSE – a few pointers for Grade 9 Understanding 2.59, 2.63B, 2.69

I have had a request from a student to write about the level of details needed in the section of the specification on human transport. Here are the relevant bullet points from the specification, together with a very brief outline of the kinds of details to learn:

- Blood composition 55% plasma, 45% cells (red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets)

- Plasma functions – transport of dissolved carbon dioxide, dissolved glucose, urea, salts etc.and transport of heat around body

- Red Blood cells – no nucleus, each cell packed full of 250,000 molecules of haemoglobin, biconcave disc shape to squeeze through narrow capillaries

- Phagocytes/Lymphocytes – two types of white blood cell, phagocytes engulf foreign organisms in blood by phagocytosis, lymphocytes do many functions in defending the body against disease but many produce antibodies

- Vaccination with reference to memory cells and primary v secondary response (see below)

- Functions of clotting and role of platelets (prevent infection, stop blood loss – platelets play central role in clotting as they produce chemicals that are needed for clotting cascade

- Structure and function of the heart (learn names of chambers, blood vessels, names of four sets of valves and what they do)

- Role of adrenaline in changing heart rate during exercise (speeds it up to maximise cardiac output to muscles)

- Structure and functions of arteries/veins/capillaries (simple bookwork)

- General plan of circulation including heart, lungs, liver and kidneys (see below)

The two sections that are perhaps hardest to interpret are the ones on vaccination and the general plan of the circulation.

1) Key terms in vaccination to understand:

- Antigen

- Antibody

- Lymphocyte

- Clonal Selection theory

- Memory cells

- Effector cells (plasma cells)

- Primary response

- Secondary response

At the end of the process, you should be able to provide a clear concise answer to the following question?

Why is it that the first time your body encounters measles virus, you suffer from the disease measles? Why will someone who has had measles as a baby (or been immunised against it) never contract the disease measles even though the virus might get into their body many subsequent times?

2) The blood vessels involved in the four organs mentioned are described below.

Heart – receives blood from the coronary arteries which branch off the aorta before it has even left the heart: Why doesn’t the cardiac muscle in the heart just get the oxygen and nutrients it needs from the blood in the chambers?

Lungs – pulmonary artery takes blood from right ventricle to the lungs, pulmonary vein return oxygenated blood to the heart and empty it into the left atrium. What is unique about the composition of the blood in the pulmonary artery?

Liver – has a most unusual blood supply. There is a hepatic artery that branches off the aorta and brings oxygenated blood to the liver. Blood also goes to the liver in the hepatic portal vein which brings blood from the small intestine. Blood in the hepatic portal vein will contain lots of dissolved glucose and amino acids, both of which are processed in the liver. Deoxygenated blood leaves the liver in the hepatic vein. Find a diagram to show the arrangement of these three blood vessels.

Kidney – straightforward blood supply in that there is a renal artery and a renal vein. (important idea is that the renal artery is much much bigger than you would expect from the size of the organs: 25% of the cardiac output of blood flows through the kidneys on each circuit) Why do you think this is?

I hope this helps – more to follow when I get home from my holidays tomorrow afternoon…..